Whether you are an early adopter, faced a shareholder resolution on the issue or just watched the action from the sidelines this year, all companies need to talk more with their shareholders about proxy access

For US companies, the hot governance topic of the year is undoubtedly proxy access. In the run-up to this year’s proxy season, more than 100 companies either received shareholder proposals on proxy access or unilaterally agreed to implement it. Just as importantly, major institutional investors and proxy advisers came out in support of opening up the director slate – though they didn’t all agree on the details.

‘With 108 proposal submissions, proxy access is the highest-profile shareholder resolution topic for the 2015 proxy season, ahead of the number of resolutions addressing topics such as climate change and disclosure of political contributions and lobbying activities, which occupied the top spots in shareholder proposal submission volume terms prior to 2015,’ says Edward Kamonjoh, US head of strategic research & analysis at ISS.

The developments open up a new set of questions for publicly listed firms in the US. Companies that weren’t targeted this year may well be in 2016. They need to work out where they stand on the issue, how vulnerable they may be to a vote and, if they did implement proxy access, what form would be most suitable for them.

Companies that have adopted proxy access, on the other hand, will wonder how it might be used. Will activists seek to exploit this new power? Could thousands of retail shareholders gang together to meet the ownership threshold? To what extent has the power balance between management and shareholders shifted?

More broadly, the question remains as to whether proxy access is going mainstream. Some have already declared this governance battle over – given the support from institutions and proxy advisers – but widespread adoption across the S&P 500 is far from a formality at this point.

Where it all began

While advocates of shareholder rights have been fighting for proxy access in the US for decades, current developments trace their origin back to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent Dodd-Frank Act, which affirmed the right of the SEC to publish a proxy access rule. In 2010 the regulator adopted a rule that followed the 3/3/25 approach: shareholders could nominate their own slate of directors if they held a minimum of 3 percent of shares for at least three years, and they could propose directors for either 25 percent of the board or one seat, whichever was greater. The rule passed in a tight 3-2 vote.

But it was struck down on appeal a year later. The Business Roundtable and the US Chamber of Commerce, two powerful business lobby groups, claimed the commission had not properly considered the economic effects of its decision, and the DC Circuit Court of Appeals agreed. The SEC and then-chair Mary Schapiro decided not to challenge the appeal, but a rule that allowed company-by-company proposals for proxy access came into effect soon afterwards. With the regulator out of the picture, it was left to companies and their shareholders to work out the issue for themselves.

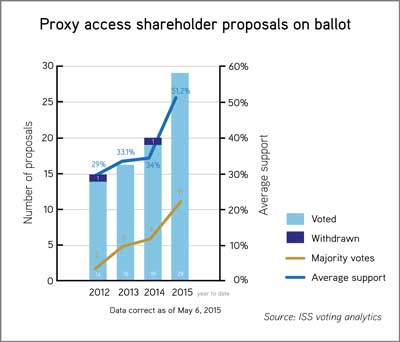

Over the next four years, the number of proxy access proposals filed by shareholders crept up (see Proxy access shareholder proposals on ballot, below). During this time, investor support continued to build for the 3/3/25 approach. ‘In 2014, 19 proposals on proxy access (the highest number of proposals at the time) were voted on by shareholders, six of which received majority votes,’ says Kamonjoh. ‘Eleven of the proposals that mirrored or closely resembled the formulation of access featured in the SEC’s 2010 proxy access rule received 54 percent shareholder support on average, whereas proposals that strayed away from the SEC’s formulation received 9 percent support on average.’

Making a splash

All of which brings us nearly up to date. One of the drivers for the sweeping adoption of proxy access this year came last September when James McRitchie, governance advocate and founder of CorpGov.net, filed a proxy access proposal at Whole Foods using the same criteria as the SEC’s original rule. Whole Foods then produced its own proxy access amendment: shareholders would have to own 9 percent of the shares for at least five years.

Whole Foods petitioned the SEC to grant it a ‘no action’ letter, which would allow it to ignore McRitchie’s proposal on the grounds that a similar proposal from the company already existed. The SEC did this. Then, in an unprecedented move, McRitchie appealed the ‘no-action’ letter – and won. Current SEC chair Mary Jo White, clearly worried the ‘no-action’ rule was being unfairly exploited by companies, instructed her staff not to offer any more opinions on similar proposals until a review had been carried out.

Around the same time, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, a governance advocate who has filed numerous proxy access proposals since 2011, dramatically increased his focus on the issue. Under a new campaign called the Boardroom Accountability Project, he filed for proxy access at 75 companies. With the no-action defense off the table and scores of companies targeted, proxy access took center stage as the main governance issue of 2015.

The final element needed to push forward proxy access was support from major institutional investors and proxy advisers. This came during January and February when updated governance guidelines displayed wide-ranging support for shareholder access to the proxy. One of the most notable changes saw ISS change its position from analyzing proposals on a case-by-case basis to generally supporting the 3/3/25 approach. Glass Lewis, by contrast, said it would continue to review each proposal on its own merits (see Where they stand, bottom of page).

Nudged into action by surrounding events, some companies have voluntarily adopted proxy access in their bylaws without receiving a proposal. These companies tend to fall into two categories: those that pride themselves on being governance leaders, such as Prudential, and those that are lightning rods for activist pressure and want to get ahead of the debate.

‘Prudential’s board is committed to upholding strong corporate governance practices,’ commented Karl Krapek, the company’s lead independent director, at the time of the announcement. ‘Based on our ongoing assessment of best practices and discussions with shareholders, we decided to take this proactive step to make proxy access available to our long-term shareholders and further strengthen Prudential’s corporate governance standards.’

On the sidelines

For companies not targeted this year, there will be plenty to discuss post-proxy season. Ron Schneider, a former proxy solicitor and current director of corporate governance services at RR Donnelley, the financial communications firm, says IROs should ask a number of pertinent questions. These include:

-How did different investors vote on this, including our largest shareholders?

-What recommendations did proxy advisers make?

-Who were the proponents? Do they own our stock?

-Do the targeted firms have anything in common?

-What are our peer companies doing?

‘What companies are going to have to do is inform their boards on this issue, just like any other emerging issue,’ says Schneider. ‘If I was a corporate board member, I’d want to know this from my IR team and corporate secretary: if we were targeted this coming year and it was a 3/3/25 proposal, how vulnerable would we be to that vote?’

One side of it is keeping your management and board informed, the other side is making sure you are effectively communicating to shareholders about your board and board selection process, notes Schneider. ‘No matter where you stand on proxy access, I can think of no reason why any company would not want to be telling its best story now: its current board members, their skills and qualifications, its director nomination process, its board re-evaluation process, its diversity,’ he says.

To identify likely targets for next year, a good place to start is the proposals submitted by the New York City Pension Funds. The public pension fund manager selected its 75 companies based on three areas: carbon-intensive coal, oil & gas and utility companies; companies with little or no board diversity, including gender diversity; and companies that received strong opposition to their non-binding say-on-pay votes in 2014. Any company that falls into one of those three categories is a likely target for the Boardroom Accountability Project’s next round of filings.

Larger companies are also more likely to be in the crosshairs. ‘It’s going to take some time for proxy access to reach beyond the S&P 500 because corporate governance activists – the public pension funds and labor pension funds – usually focus their efforts on large-cap companies,’ says Ted Allen, director of practice resources at NIRI and former governance counsel and director of publications at ISS. ‘The labor pension funds, typically, are indexed to the S&P 500 and their holdings among the smaller companies are more scattered.’

One warning is that it may become harder for companies to negotiate as proxy access spreads. Partly that’s because a stronger consensus will form around best practice. But it’s also because governance advocates are keen to implement as much proxy access as possible early on to get the ball rolling, and so may give companies less leeway as time goes on. McRitchie refers to this as giving companies a pass. Speaking to IR Magazine in March, he said: ‘Talk to the proponent and your other shareowners. Proxy access is ‘on sale’ this year with opportunities that might never come again.’

Allen cautions that companies will need good reasons to stray from the 3/3/25 approach. ‘If a company wants to adopt a threshold that’s more onerous than the 3 percent for three years with a 25 percent cap on seats that can be sought by activist nominees, the IR team is going to have to work hard to make the case that the company’s unique circumstances merit a higher threshold, because a consensus is emerging among institutions in favor of the 3 percent/three-year standard,’ he says.

New powers

Those that have now adopted proxy access will be wondering how it might be used. But that is not an easy question to answer, given the few companies that had implemented it pre-2015.

One place to look for further information is overseas markets, where proxy access is already available (see Proxy access around the world, below). The example of Canada suggests proxy access will be of limited interest to investors: its proxy access rule has been used only once in three years, according to a CFA Institute report published last October.

Few worry that proxy proponents will be hijacked by activists focused on quick financial returns, given the length of holding period thresholds. There is some talk that SRI investors could use it to put like-minded people on the board; others wonder whether thousands of retail shareholders could gang together on social media to submit a crowd-sourced board slate. The possibilities will be slightly different for each company, depending on which criteria its version of proxy access operates under. For example, some are putting caps on the number of shareholders that can group together to meet the ownership threshold.

The generally held view is that it will be used very infrequently. ‘It’s more likely to be used as leverage when investors are engaging with the company about refreshing the board and trying to get a company to consider their suggestions for new board members,’ says Allen. ‘With proxy access in place, investors know they have something to use if a company is unwilling to consider their suggestions.’

He also says it doesn’t serve much use unless you are the kind of investor that can then go on to win the vote. ‘It’s kind of pointless if you nominate somebody and then don’t have the resources to do a PR campaign to lobby other investors to support the nominee,’ he explains. ‘If proxy access were to become widespread, I think you’d see perhaps one or two cases a year, involving companies that are already in the doghouse with corporate governance activists.’

Going mainstream?

Market commentators are fond of calling ‘tipping points’, but have we reached one with proxy access? It is hard to argue against. Given the way investors and proxy advisers have fallen into line over the issue, plus the voluntary adoption by a number of governance-conscious companies, you can expect advocates of access not to take their foot off the gas in 2016. Stringer certainly has his eyes on broad adoption. He called the 75 resolutions filed last winter ‘a major first step to roll out proxy access across the market’.

But much depends on the voting results of this year’s proxy season. ‘If we see average support levels above 50 percent, it suggests a long-term trend where these bylaw provisions will become widespread, particularly at firms with large institutional share ownership,’ says Allen.

Many see similarities between the spread of proxy access and other governance developments driven by direct engagement, rather than a blanket regulatory rule. ‘The issue is in its early stages,’ says Schneider. ‘Majority voting in director elections has been growing gradually over the last decade, and I think the same will happen with proxy access. It’s going to be a multi-year or even decades-long march.’

Proxy access around the world

Evidence from other countries suggests that proxy access, when available, is rarely used by shareholders.

Last year CFA Institute released a report using data from governance adviser Manifest that investigated how often proxy access was used in Canada, Australia and the UK over the preceding three years. The report finds:

-Canada – used once in three years (successfully)

-Australia – used 11 times in three years (once successfully)

-UK – used 16 times in three years (eight times successfully)

The data suggests that ‘proxy access is a rarely used shareowner right that is typically used only when other outlets for shareowner concerns about a company or its board – such as engagement between shareholders and companies – have been exhausted or have otherwise proved unfruitful,’ state the authors in the report.

Dueling votes

Following the SEC’s decision not to offer an opinion on competing proposals, a handful of companies ended up with the interesting situation of having shareholders vote on two proxy access proposals: one proposed by governance campaigners and the other by management.

In the cases of AES Corp and Exelon, the management proposals had a higher ownership threshold (5 percent) and a lower cap on board nominees (20 percent of the board) than the shareholder proposals, which followed the 3/3/25 approach.

Highlighting the fact that there is no firm consensus yet on how proxy access should be implemented, at AES two thirds of shareholders supported the external proposal, while at Exelon 52 percent came out in support of management.

The results also underline that each company presents a different set of circumstances – in terms of management credibility, financial performance, governance record and so on – all of which need to be taken into account when analyzing how a vote could play out at your company.

Where they stand

Institutional investor and proxy adviser policies on proxy access

BlackRock

‘We believe long-term shareholders should have the opportunity, when necessary and under reasonable conditions, to nominate individuals to stand for election to the boards of the companies they own and to have those nominees included on the company’s proxy card…

‘Proxy access mechanisms should provide shareholders with a reasonable opportunity to use this right without stipulating overly restrictive or onerous parameters for use, and also provide assurances that the mechanism will not be subject to abuse by short-term investors, investors without a substantial investment in the company, or investors seeking to take control of the board. We will review proposals regarding the adoption of proxy access on a case-by-case basis.’

Source: BlackRock’s proxy voting guidelines for US securities

CalSTRS

‘Companies should allow shareholder access to the director nomination process and to the company’s proxy statement. Generally, CalSTRS believes a long-term investor or group of investors owning in aggregate at least 3 percent of the company’s voting stock for [at least]three years should be able to nominate a minority of the directors on the company’s proxy statement.’

Source: CalSTRS’ corporate governance principles

Council of Institutional Investors (CII)

‘Access to the proxy: Companies should provide access to management proxy materials for a long-term investor or group of long-term investors owning in aggregate at least 3 percent of a company’s voting stock, to nominate less than a majority of the directors. Eligible investors must have owned the stock for at least two years. Company proxy materials and related mailings should provide equal space and equal treatment of nominations by qualifying investors.’

Source: CII policies on corporate governance

Glass Lewis

‘Glass Lewis believes significant, long-term shareholders should have the ability to nominate their own representatives to the board… Glass Lewis does not have a preferred number/percentage of directors that may be nominated through the proxy access procedure as we recognize the appropriate level may vary depending on many factors.’

Source: Glass Lewis

ISS

‘ISS will generally recommend in favor of management and shareholder proposals for proxy access with the following provisions:

-Ownership threshold: maximum requirement not more than 3 percent of the voting power

-Ownership duration: maximum requirement not longer than three years of continuous ownership for each member of the nominating group

-Aggregation: minimal or no limits on the number of shareholders permitted to form a nominating group

-Cap: cap on nominees of generally 25 percent of the board.’

Source: ISS

T Rowe Price

‘T Rowe Price believes significant, long-term investors should be able to nominate director candidates using the company’s proxy, subject to reasonable limitations comparable to those contained in the SEC’s 2010 proxy access rule… We support proposals suggesting ownership of 3 percent of shares outstanding as the standard for access to the proxy. We also support a minimum two-year holding period, with a maximum of three years. We do not believe there should be significant impediments to a proponent’s ability to aggregate holdings with other shareholders in order to qualify for access to the proxy.’

Source: T Rowe Price’s proxy voting policies

TIAA-CREF

TIAA-CREF believes ‘shareholders should have the right to place their director nominees on the company’s proxy and ballot in accordance with applicable law, or absent such law if reasonable conditions are met. The board should not take actions designed to prevent the full execution of this right.’ The investment company also sent a letter to its 100 largest holdings, stating its support for the 3 percent ownership threshold.

Vanguard

‘We believe long-term investors may benefit from having proxy access, or the opportunity to place director nominees on a company’s proxy ballot… [We] also believe proxy access provisions should be appropriately limited to avoid abuse by investors that lack a meaningful long-term interest in the company... We generally believe a shareholder or group of shareholders representing 5 percent of a company’s outstanding shares held for at least three years should be able to nominate directors for up to 20 percent

of the seats on the board.’

Source: Vanguard’s proxy voting guidelines

This article appeared in the summer 2015 print issue of IR Magazine