IROs at listed buy-side firms talk about IR in the investment management sector

With its industry-savvy audience, low disclosure expectations and a forthright, cash-generative business model to spell out, implementing an IR program at a listed asset management firm may appear like a dream job to the average investor relations professional. But the usual tasks of communicating strategic information to the outside world when you’re in the business of selling funds might feel a bit schizophrenic at times, as you sit on the fence between your own portfolio managers and investors.

So how do these IROs manage the complexity of having actual or potential business partners and competitors as their main audience – and why did their company choose to list in the first place?

Working in investor relations for a listed buy-side firm doesn’t differ much from the fundamental role an IRO at any other firm would have, says Brian Sevilla, who heads the investor relations team at Franklin Resources, the holding company for global investment management firm Franklin Templeton. ‘But there are certainly different expectations and different conversations,’ he adds.

Like any sector, asset management has its own product set and specificities, the first being that it is a highly relationship-driven industry. ‘It’s definitely an interesting ecosystem being in the financial services sector, and particularly asset management, because everything is really intertwined, and there are multiple layers of relationships,’ Sevilla explains. ‘As a business, we build a relationship with advisers and clients and, because we’re a public company, also with investors and sell-side analysts.’ The latter category is often part of an investment bank seeking to sell its trading, treasury or advisory services.

‘Working for an asset manager, you’ll find everyone connects,’ confirms Shelley Fishwick, group head of investor relations at UK-based Aberdeen Asset Management. ‘You’re managing assets on behalf of pension funds and charities or third-party assets for private banks, so you’re inevitably going to have competitors within parts of your business area.’

This is a reality well illustrated by Sevilla, who jokes that you would never see an engineer from Google walk into a meeting at Apple to talk to the CEO – unless he or she was trying to get a job there. ‘The paradox of our sector is that every day our competitors, both private and public, may come in and have a meeting with our chief executive, because they want to do an investment on the fund side,’ he says, adding that these interdependent relationships don’t affect his day-to-day job. ‘You know they’re there, but you’re so accustomed to it that you don’t think twice about it.’

Worlds apart

For Vittorio Pracca, from independent Italian asset management firm Azimut, prudence is always de rigueur when it comes to his relationship with the firm’s investment team. ‘The interaction I have with our portfolio managers is very limited because I don’t want to mix up the two worlds,’ he says, pointing out that the analysts covering his firm are probably in a more awkward position than he is. ‘They have this issue that we are ‘clients’ on both sides because part of their job will be to go and pitch to our portfolio managers to buy other companies.’

This doesn’t seem to have affected the good relationship and ‘open dialogue’ Pracca maintains with the sell side, nor has it lessened the strong attention his company receives from analysts and potential investors, especially those from the UK. ‘Unlike a bank or an insurance company, we don’t have any balance sheet risk and our margins are very high, so our business is a very cash flow-generative one,’ he says, describing the IR activities at his €2 bn ($2.7 bn) market cap firm as ‘quite intense’.

When meeting with stakeholders, Pracca certainly values the relative straightforwardness he experiences in getting the company message across. ‘The positive side of being an IRO for a company in the financial services industry is that our audience knows the business very well because we are in the same sector and we speak the same language,’ he highlights. ‘They know the basics, which is an advantage for us, in the sense that we don’t have to focus on what we do as a business, but mostly on how we do it and how we differentiate ourselves from other players.’

‘There’s still a challenge in the education that takes place about our products and services in different countries, as people have a bias toward what they’re familiar with,’ adds Sevilla. ‘There is also definitely an expectation that we are more knowledgeable about the capital markets because that’s our product. That said, there are clear benefits to being an asset management company that is public, because as an asset manager we understand what it is our investors are trying to do.’

Information edge

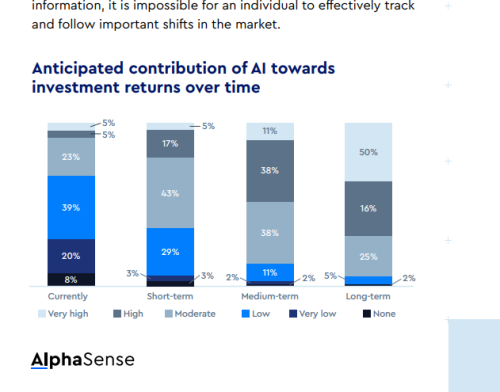

Sevilla cites another significant upside as having access to state-of-the-art technology in terms of competitive information. ‘The IR team gets to play with the same tools our portfolio managers have,’ he reveals. ‘So I have access to all the premier data service providers, which I can use to do my own research on our peers.’

Furthermore, Sevilla believes it’s this distinctive availability of information that makes asset management a unique sector in terms of IR. ‘A particularity of our industry is that it’s probably the most transparent one out there,’ he says. ‘Our audience isn’t waiting for us to disclose something at a corporate level, because there’s a world of publicly available data on flows and on our funds, where you can see how they’re performing daily, and also against their peers.’

‘If you’re not performing, word travels pretty quickly,’ agrees Fishwick. ‘But obviously if you’re doing IR for any corporate, what you’re looking at is not only what the components of your businesses are doing, but also all the other aspects in terms of your cost base.’

She points out that asset managers are expected to perform well when markets are strong, because good market conditions support their revenues and generate significant levels of cash, which in turn make them attractive businesses. ‘This means our model is relatively straightforward, as opposed to other, more complex sectors,’ she adds.

‘Asset management is a very good business model because you have a recurrent revenue stream and it’s not capital-intensive,’ agrees Sevilla.

Smart moves

Whatever the rationale behind their company’s IPO – reducing the leverage after an MBO at Azimut, funding an acquisitive strategy at Aberdeen, or simply creating a liquid market for the stock at Franklin Templeton – Pracca, Fishwick and Sevilla all agree that opening up through an IPO has been a good strategic move for their company, especially in terms of retaining the right people in and around the firm.

‘We can now offer shares of a listed entity to our top management, employees and network of agents who became shareholders in the company after the buyout,’ Pracca points out. ‘This pool of capital also constitutes a very interesting tool to attract new advisers and agents.’

‘The reason any company tends to be listed is to tap into the stock markets to borrow funds in order to implement a strategy, particularly when companies are smaller, in order to get to a level where they can stand on their own two feet,’ adds Fishwick.

‘Like in any industry, there’s good and bad that comes with being a public company,’ says Sevilla. ‘The good is that a liquid market for your stock can be an effective vehicle for things like retention of employees, and part of compensation plans. The drawbacks are that everything you do is under a microscope and you have to deal with the compliance and the reporting – the challenges that any other public firm will have.’