What’s it like doing IR in the nuclear industry?

The word ‘nuclear’ has interesting connotations. No one has ever threatened a ‘coal holocaust’ or to drop ‘methane bombs’ on enemy cities, so what is IR like for an industry where some investors see cheap, clean, endless power, and others see Chernobyl smoldering in the sunset?

‘You can read a lot on this topic, sometimes from sources that are not necessarily well informed’ – Marie de Scorbiac, Areva |

After the Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown following the Japanese tsunami in 2011, Germany closed down its entire nuclear power sector. Britain and the US continued with plans for nuclear power to save carbon. Siemens, which built all 17 of Germany’s reactors, exited its worldwide nuclear equipment business in what its CEO called ‘an answer’ to public disquiet. ‘Fukushima will be an occasion to exit, but not its reason,’ a Siemens senior executive told the Financial Times at the time of the decision.

French giant Areva, however, has no plans to quit the industry. ‘Investors tend to look at nuclear like any other market,’ says IRO Marie de Scorbiac. ‘They are looking for growth perspectives and, in that respect, nuclear is a card to play. Even so, they’re always influenced by the headlines, which can differ from one country to another, considering that nuclear safety is a common requirement for all the investors.’

The IR department has to deal with this a lot, she laments. ‘You can read a lot on this topic, sometimes from sources that are not necessarily well informed,’ she says. ‘We have experts at Areva who provide solid analysis on the subject, and part of the IR job is to ensure they correctly understand.’

Even in pro-nuke France, Areva does deal with some professed socially concerned investors. ‘The few we talk to do raise it in their first approach, but we point out that Areva is only present in civil nuclear,’ notes de Scorbiac. ‘We do as much as we can to educate them on the benefits of nuclear and that the group’s development strategy relies on the three main principles: safety, security and transparency.’ She also points out that people ‘usually focus on our historical nuclear activities and forget about renewables. Though it represents only 6 percent of our revenues currently, it is a growing business that’s complementary to our nuclear activities.’

Areva doesn’t shy away from the nuclear issue: it raises it pre-emptively with investors. ‘Opportunities in the nuclear sector are inevitably linked to public acceptance, which is not possible without clear and transparent communication about the sector,’ explains de Scorbiac.

Positive energy

By contrast, it has been many decades since anyone built a new reactor in the US; and in 20 years or so, even with operating license extensions, present reactors will be obsolete and represent all cost and no revenue. That said, the Obama administration is encouraging a nuclear renaissance, offering loan guarantees, development grants and long-term help with waste.

Apart from the emotion and politics, the economic and business issues raise almost as many questions as answers. Reactors involve huge fixed costs, with a tendency to overrun, and the waste-disposal expenditure stretches out with half-lives way beyond the investment horizon of even the most far-sighted pension fund. And while Fukushimas might be few, they are spectacular and expensive, so at least some shareholders fret.

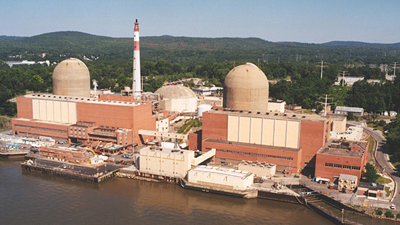

At this year’s annual meeting of Entergy in May, the board defeated a shareholder motion from the Office of the New York State Comptroller urging a faster move of spent nuclear fuel from spent fuel pools to dry cask storage at its controversial Indian Point complex on the banks of the Hudson, very close to New York City. Paula Waters, vice president of IR at Entergy, which operates 11 other plants, says that as ‘nuclear generation is such a significant part of our business, naturally it’s an area of interest for our shareholders, and we share the same priority: a commitment to operating our nuclear units at the highest levels of safety, security and reliability.’

Entergy’s Indian Point Energy Center on the Hudson

Even so, the Fukushima event I focus investors’ attention: TEPCO, the Japanese company that owns the Fukushima plant, struggles with insolvency because of the trillions of yen the meltdown will ultimately cost. ‘In the immediate aftermath, the focus was on the stringent design and construction standards of our facilities as well as the ongoing programs to ensure plant safety,’ says Waters. ‘Over time, investors turned their interest to the operational and financial ramifications of new and pending regulatory requirements.’

Indeed, as much as nuclear safety, institutional investors are interested in the financial viability of merchant nuclear facilities, Waters states, especially ‘in the wake of low natural gas prices and the recent announcement of two nuclear plant closures.’ Merchant plants sell power to the highest bidder rather than at regulated rates, which was great when energy prices rose, but could point to financial meltdown when cheap natural gas flooded the market.

Entergy’s IR response is that, as the firm can’t control what power prices do, it focuses on factors it can control. ‘We’re looking for ways to improve efficiency and productivity,’ says Waters. ‘We’ll look at what we can reasonably do to maintain the viability of these plants while keeping safety and security as our top objectives.’

On the pre-emptive front, Entergy also highlights its place in indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, Target Rock’s 2013 Sustainable Utility Leaders Index and the Carbon Disclosure Project Leadership Index, which lists companies with the highest carbon disclosure scores.

No safety in the numbers

Safety was not the issue, but Virginia-based Dominion Resources had to cope with increased investor scrutiny when it decided to close the Wisconsin Kewaunee reactor it had bought in 2005. Tom Hamlin, Dominion’s vice president of financial analysis and IR, explains: ‘The reasons were financial. Dominion has one of the best operating records in the country for nuclear.

‘Before the shutdown we had seven plants and the economics are still sound, even with the decommissioning. The Kewaunee plant was unique, part of a plan to build a strategic portfolio of four or five nuclear plants, which would offer economies of scale. But we were outbid and left with that unit. We tried to sell it when we got the license extended but we couldn’t get investors interested in it.’

Apart from the numbers, in the wake of Fukushima, Hamlin comments that potential shareholders scrutinize safety rather than political correctness. ‘The US utility industry has done a tremendous job in improving its operating record,’ he observes. ‘It’s been a long time since Three Mile Island.’

He invokes a recent 5.8 intensity earthquake in Virginia, ‘just 25 miles from our North Anna nuclear plant. It was shut down as a safety precaution, but a very thorough inspection showed the design had held with virtually no damage.’ In fact, Dominion is considering building new nuclear plants.

But while it might be safe, is it attractive to investors in a traditional way? ‘Absolutely!’ says Hamlin. ‘It’s very low cost. One of the reasons our service area is so competitive is that our power costs are so low. In our regulated area here in Virginia we have four nuclear units providing 40 percent of our energy. It’s very competitive.

‘We’ve had no protests from investors about nuclear. We tend to deal with institutional investors and we don’t come across committed SRI investors, certainly not on the nuclear power issue. We find it more with folks who ask about carbon use or energy efficiency.’

Indeed, the environmental issue can even provide green leverage in securing investor attention because, as Hamlin points out, the issue of the carbon footprint ‘has proven bigger than nuclear, which is one of the best ways to reduce it.’