Female IROs are increasing in Europe and women already dominate IR in emerging markets, but senior IR roles still tend to go to men in many markets, and women earn less. Are women treated differently from men in IR?

Over the decades, women in the workplace have been associated with several less than prestigious activities. These days, however, more and more women across Europe are turning to IR. It may be a stereotype, but most people view women as good communicators who are strong on networking, precision and presentation, leading many to view IR as a natural career choice for women.

‘The City can be pretty soul-destroying for women so they typically will try to get out of that and into IR,’ says Heather McGregor, CEO of IR recruitment consultants Taylor Bennett, who adds that most female IROs in the UK have financial backgrounds.

But if women are so cut out to be great IROs, one might wonder why they are only now coming to IR, rather than since the inception of the industry. One reason is that IR is a relatively new profession in many European markets.

‘Now the job description is better known, there is more of a natural pull for women,’ explains Vienna-based Pankl’s head of IR, Heidrun Ekhart. She admits that, until recently, IR was seen as more of a male profession in Austria. ‘But at investor conferences I now see many women doing the job,’ she notes.

Even in Germany, Denmark and Belgium, which are still dominated by male IROs (see IR societies’ female members, right), female IRO numbers are increasing more rapidly than their opposite-sex counterparts. Patrick Verelst, head of Belgian IR society BIRA, sees this as a reflection of increasing female visibility in other jobs in the financial markets, such as portfolio managers, analysts and traders.

Secretarial support

Closer examination shows it may be too soon to champion female finesse in the world of IR, because an increase in numbers does not equate to superiority in position. Take French IR society CLIFF, for example, which has seen a significant rise in female members since its founding 20 years ago. The proportion of female members grew from an initial 13 percent to 30 percent 10 years later, and today an overwhelming 56 percent of CLIFF’s members are women.

Despite IR’s swelling popularity with women, however, CLIFF’s head Eliane Rouyer points out that IR teams, while growing in size, are not necessarily acquiring female chiefs. Female IROs are building up teams, but Rouyer estimates that only a third of IR heads at CAC 40-listed companies are women.

It’s a similar story in Ireland. Bank of Ireland’s Louise Hendrick, winner of best IRO at the recent IR Magazine Ireland Awards, is an exception with her four-strong women-only IR team. Hendrick admits that, in Ireland, men tend to occupy more senior roles in IR, adding that ‘meetings are usually male-dominated.’

Even in the UK, where there is a pretty even split between male and female IROs, investors and analysts have consistently voted for men as best IRO over the past four years. The winning teams, on the other hand, frequently comprise women. IR magazine’s Nordic and continental European awards tell a similar story.

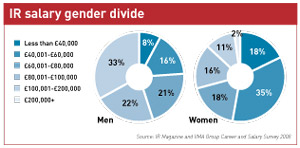

The abundance of women in supporting IR roles could be down to the fact that female IROs tend to be younger. Women IROs have an average age of 37, while male IROs have an average age of 40, according to the salary survey IR magazine recently produced in association with VMA Group. The lower age band also helps to explain why women tend to attract lower salaries in IR (see IR salary gender divide, right).

Grabbing opportunities

While men tend to occupy more senior IR positions in the more developed western markets, it’s a different story for recent market openings. Now IR has gained recognition, there is space for women to seize opportunities that would have previously gone to men.

Smaller companies, new to the IR profession, provide the perfect opportunity for women looking to step into more dominant roles: 9 percent of women (compared with 2 percent of men) questioned in the salary survey were taken on specifically to create an IR function. Hendrick agrees that a viable step-up for a female IR professional would be to move to a smaller company and give the IR function shape, as Isabel Lutgendorf did at Clipper Windpower (see New-age IR, May 2008).

Emerging markets are also attracting a preponderance of senior female IROs. Unlike their western counterparts, Bulgarian IR professionals tend not to come from broking or analyst backgrounds where men are more visible, according to Bogomila Hristova, head of Bulgarian IR society BIRS. ‘Local IROs come from accountancy, finance management, public relations or corporate secretary positions, which are dominated by women.’

The work itself varies in younger markets. ‘Bulgarian IR activities began with preparing and communicating information about the company, and managers considered women more appropriate for this,’ explains Hristova.

Iceland has another female-dominated IR association, headed by a woman. Its current chair, Vala Pálsdóttir, who is also head of IR at Glitnir Bank, explains that women have always played a dominant part at the Icelandic group.

Maternal instinct

Pálsdóttir admits, however, that at least five Icelandic female heads of IR are taking maternity leave this year, including herself – ‘and we represent almost 10 percent of our association,’ she says.

Although women are choosing to start their families later in life these days, it can still affect their work as IROs. ‘It’s not always easy,’ admits Ekhart. ‘I have a baby and it can be tricky on roadshows when you have to travel a lot.’ Luckily for her, Pankl is a small company so there is less travel involved. ‘You can plan ahead for the few days a year when you have to be there at 6 am for results,’ she adds.

Women typically view IR as more of a long-term position than men, as there is a certain degree of predictability about IR that allows women to manage families. Some 34 percent of women anticipate staying in IR for more than five years, compared with only 19 percent of men, according to the salary survey. In fact, 27 percent of male IROs foresee staying in their current position for less than two years, compared with only 13 percent of women.

This could mean women take IR more seriously and are more devoted to the position and to building up their relationships with their shareholders. Others might argue that women are simply not as ambitious, and the salary survey seems to bear this out: only 7 percent of women – compared with 15 percent of men – saw themselves stepping into the CEO’s shoes at a future date. The CFO position is more realistic for both women and men, but yet again the number of aspiring women (13 percent) pales in comparison to the number of aspiring men (31 percent). One reason for this lack of ambition could be a scarcity of opportunities. ‘It’s still harder for a woman to jump to a CEO or CFO role,’ remarks Ekhart.

Although there is plenty of scope to move around within IR, senior management is usually male-dominated in the UK, too, according to one female IRO at a FTSE 100-listed company: ‘It’s easier to move up if you’re a man.’

McGregor can cite several examples of women who have gone on to be head of global communications or strategy. In spite of these lofty promotions, however, most women stay put in their investor relations position – unlike men, who do not have the same procreative restrictions and so are freer to dip in and out of roles.