Talking to Kim Shannon of Sionna Canadian Equity Fund

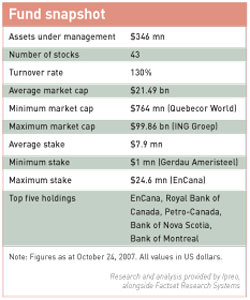

Kim Shannon studied archaeology at the University of Toronto, but a lifetime of working for under-funded academic projects was a dismal prospect. ‘So I decided to live in the real world,’ she says, laughing. Shannon now runs several funds for Sionna – the Gaelic word for her surname – and the Canadian Equity Fund is her flagship vehicle, a $384 mn large-cap fund packing in more than 40 stocks.

Based in Toronto and the owner of Sionna Investment Managers, Shannon has worked in the fund management industry for almost 25 years. Her mentor, the highly regarded investor John DiTomasso, once said the secret of value investing was to risk looking like a bit of a tramp while waiting for a stock to come back.

‘Well, John is a much more aggressive manager than I am,’ says Shannon. ‘He buys some pretty unlovable stuff and, with his analysis and formidable patience, he usually wins in the long run. I try to be a very consistent performer, with little exposure to small caps. The majority of my stocks are energy and financials, about 30 percent each.’

As a deep-value investor, does Shannon feel knocked back in bull markets like the current one? ‘Year to date, sure,’ she concedes. ‘We do okay with a medium time horizon.’ This horizon is generally two years plus. Shannon’s stocks are the beaten-down and ugly ones for which she anticipates a 30 percent return within two years – and the strategy works. Her fund consistently beats the S&P/TSX Composite Index over the long term. Compounded returns between 1997 and 2006 average 16.2 percent a year.

But finding cheap stocks right now is difficult, Shannon admits. ‘There isn’t much around that’s really cheap,’ she notes. ‘Natural gas prices are low and drilling and oil service stocks are weak. You just have to be patient.’

Despite the conservative portfolio – her top three holdings are EnCana, Royal Bank of Canada and Petro-Canada – Shannon uses regular broker meetings to investigate new investment openings. But she wants decent dividends, a low P/E and a clear and consistent story about the numbers.

‘The classic challenge at such meetings is that management increasingly hides behind the quotation ‘competitive information’. One Canadian company gives you only revenue and profit,’ she says. ‘The income statement is three lines! If you ask for details on debt covenants, you don’t get it. Or the internal hurdle rate for acquisitions. Maintenance cap ex – these entries are often a bit blurry, or fudged. We’re always asking for that one.’

Safety in numbers

Unlike some fund managers, Shannon doesn’t mind group meetings at all. Indeed, she feels they present a chance to get another view – even sometimes using group pressure to force management to come clean.

‘Sometimes you can shame management into telling you something when there is a room full of investors,’ she explains. ‘Why won’t it do this or that? I’ve seen it happen. Sometimes you want to ask an impertinent question. You might not get an answer, but you want to see how management deals with it. Or someone else might ask those questions for you in a group meeting.’

It’s an honest admission. Some fund managers can be a bit proud about group meetings and the value of following other managers’ agendas. One-to-one meetings, of course, are always useful, especially when you’re eyeballing a tyrant or a thief. Shannon remembers tackling Robert Maxwell about some particularly aggressive figures; Maxwell was a master of distracting behavior when the questions didn’t suit.

‘I had sat down with him and the earnings per share had literally halved from the preliminary red herring prospectus to the final prospectus at Mirror Group,’ Shannon recalls. ‘His reaction was, How dare you question my integrity! Clearly you don’t know about English accounting rules!’

Shannon says most company IR presentations are highly professional. But the inevitable question – the difference between US and Canadian IR – can no longer be put off. ‘The really international IR guys from the US can be more dynamic, informative and better at presenting than their Canadian counterparts,’ she notes.

Taxing issues

What has distinguished Canada from other capital markets is the hugely acrimonious income trust issue, which prime minister Stephen Harper has now attempted to squash. This issue focused on a tax loophole that, at one point, allowed 12 percent of Toronto Stock Exchange-listed companies to convert to a structure that allowed income to flow directly to the investor, neatly side-stepping double taxation. It did wonders for dividends, as well as IPOs.

as IPOs.

However, companies that converted to an income trust structure have now been given three years to switch back. ‘It was certainly the right thing to do, but it has slowed down growth in our capital markets,’ Shannon says. PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts Canadian IPO activity will hit its lowest for a decade as a result of the debacle.

On the plus side, Canada is a nation with little consumer debt, especially compared with the US and the UK, whose consumers increasingly appear to swim in the stuff. If the Canadian economy holds up, Shannon’s basket of unfashionable stalwarts are likely to continue to deliver solid yields and growth.

She’s optimistic – and not just for the medium term. ‘We have one of the most resource-intensive markets in the world,’ she points out. ‘We’re in what you would call a sideways market, which is what happens when P/E multiples fall and commodities rise. Typically they last 15-30 years. I reckon we’re now at about year seven.’