Are any IR professionals having an easy ride in this time of global market volatility, widespread recession and extreme currency fluctuations?

IROs have been stretched to the limit recently. Crises and recessions have been prevalent across most global markets; currencies have been hugely volatile, which has had a disproportionate effect on exporters, importers, companies with international shareholders or international business activities – in other words, almost everyone; and internally there has been pressure on IR departments’ budgets and spending, making it even tougher to do a more demanding job well enough to satisfy a more demanding investment community.

Expressions of sympathy aside, what else might help the weary IRO find job satisfaction? Flip answers may include ‘Move to China/Canada/Australia/Brazil’, or any other market expected to do better than the rest in coming years.

That’s probably not a realistic proposition for most (what with children at school/spouses unwilling to move/immigration rules/new language barriers), but job satisfaction might be easier to find at certain kinds of companies, regardless of where their head office is.

In that spirit we decided to try to track down some IROs whose corporations are less subject to the vagaries of macroeconomics and whose shareholders are therefore a little less edgy – perhaps even content. Take Serco, a UK-headquartered FTSE 100 stock whose IR is headed by Stuart Ford.

The UK certainly hasn’t been recession-free, and Serco is a big exporter so it’s easy to assume that currency issues would have got in the way of the company’s IR.

But Serco is an idiosyncratic company – and not just because it has a strong balance sheet, growing revenues, an annually rising dividend and the prospect of lots of future opportunities.

The company’s basic business is providing outsourced services to governments in areas including transport, aviation, justice, immigration, health, defense and business processes. Any of those might be subject to the vagaries of the market if Serco was providing them direct to consumers. But it isn’t.

‘Most of our business is government-related,’ explains Ford, who notes that in the current climate of budget deficits Serco’s customers are increasingly turning to outsourcing to help reduce costs and reform their public services.

‘And it’s mostly federal government business. Very little of it is local or state government or commercial.’ That means the company is in the unusual position of actually benefiting from austerity measures.

Moreover, Serco generates just under half its revenues from outside the UK (15 percent-16 percent from the US). ‘But our operations in continental Europe are minimal, so we’re not exposed to the euro,’ says Ford.

Nor does the company have any direct exposure to consumers, so recession and austerity measures in continental countries have no negative impact.

All of this means Ford, his colleagues and Serco’s management team are rarely troubled by questions of a macroeconomic nature from investors at home or abroad.

Eye of the storm

That’s an unusual position to be in for a European IRO, as became clear in a story we ran earlier this year (see How is the European debt crisis affecting IR, December 2012). For that story we talked to, among others, Sébastien Martel of Sanofi and Gunhild Grieve of RWE, both dealing with life in the eurozone and all that entails.

Many IROs in their position have found the macroeconomic turmoil nothing short of irritating, as it’s dissuaded many members of the investment community from taking anything much into account aside from macro matters.

As Grieve told us then, it was proving difficult for investors to look at company fundamentals, not least because share prices were no longer reflecting them.

Martel echoed Grieve’s comments, telling a story of a US investor having to reduce his European exposure – whatever the fundamentals of the individual stock – in response to an edict from his institution’s asset allocators.

An ill wind

But a recent story in the Financial Times demonstrates why things are not quite so simple, and why individual companies differ, even if they are all in the same currency zone. Indeed, some are doing especially well precisely – or at least partly – thanks to the decline in the euro. And one of those cited in the FT story is Sanofi.

Martel confirms that the company’s fortunes are rather better than they were when we last spoke. But there are lots of reasons for that, and to distil them down to the euro/dollar exchange rate is a massive oversimplification.

He talks about a number of factors that have improved the investment story for Sanofi, some macro in nature, some specific to his company.

‘If I look back a year ago there were fairly significant worries about the euro and the eurozone,’ recalls Martel. ‘Since then, despite everything that’s still going on in the eurozone, the worry investors had about the survival of the euro itself has lessened. Actions by the European Central Bank and Europe’s political leaders have reassured the markets that the euro will be defended.’

That’s helpful but it’s far from a complete cure for the anxiety being suffered by investors. ‘If you look at the pharma sector specifically, there was a shift from worry about the euro itself to worry about western European recession and austerity,’ says Martel. ‘After all, in the pharma market, a fair amount of the drugs are paid for by governments.’

So the question became: of all the companies in the sector, what is each player’s exposure specifically to the western European pharma market?

In Sanofi’s case, the answer is ‘relatively small’. ‘Almost 32 percent of our reported sales are in emerging markets,’ explains Martel. ‘That’s our leading position. Next is the US, with 31 percent and only then comes western Europe, with just 24 percent.’

Diverse business

Moreover, Sanofi’s broader strategy to some extent protects it from the government austerity that dogs some of its peers. ‘Our CEO’s strategy is one of diversification,’ says Martel.

‘We are not just in the prescription drugs segment; we are also in OTC medicines, animal health, vaccines, and the field of rare diseases. These areas are less susceptible to changes in government spending, more susceptible to consumer behavior.’

And that’s a good thing, because consumers tend to go on buying the same headache pills, the same flea powder for their dogs. Sanofi’s OTC medicines sales, for instance, have grown by two and a half times over the past four years.

The third factor removing negatives from Sanofi’s investment story is what Martel describes as ‘the very nice tailwind from the euro/dollar exchange rate’ in the first half of this year.

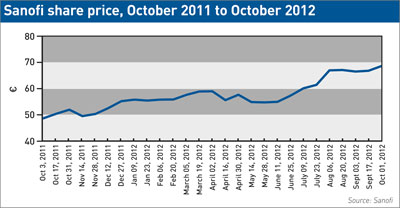

Overall, the company’s share price has risen by 40 percent over the past year – more than enough to counteract any euro weakness, and enough to provide plenty of positives to talk about with investors and analysts.

That all adds up to Martel sounding pretty darn cheerful. He’s not the only European IRO in a good position, of course; there are also good stories to tell at many of Europe’s luxury brands – German car makers BMW and Daimler, and Italian designer eyeglass manufacturer Luxottica, to name a few.

Volkswagen, too, saw its operating profits up €500 mn ($647 mn) in the first half of 2012 as a result of the downturn in the euro. But what about on the other side of Atlantic? Are there contented IR professionals in Canada, for example?

Northern exposure

We asked Rudy Sankovic, head of IR at TD Bank, the company that swept the board at the IR Magazine Canada Awards 2012 in Toronto, back in February.

Of course, he might still be grinning from his spectacular success at that event – TD Bank won six awards – but we asked him specifically whether macroeconomic factors were getting in the way of his IR program. ‘All Canadian banks have the same headwinds,’ Sankovic responds. This has nothing to do with a weak Canadian dollar; on the contrary, the loonie has been close to or above parity with the US dollar for the past few years.

‘All Canadian banks have the same headwinds,’ Sankovic responds. This has nothing to do with a weak Canadian dollar; on the contrary, the loonie has been close to or above parity with the US dollar for the past few years.

Rather, Sankovic identifies the following issues: a low interest rate environment; high levels of consumer debt, partly because house prices have doubled; highly indebted consumers, as a result of low interest rates; knock-on effects from the Europe crisis; and the US regulatory environment.

‘All investors look at Canadian banks as having the same problems,’ says Sankovic. ‘But we at TD have done a good job of explaining how we differentiate ourselves. For instance, we’ve grown our US platform and now have an avenue of growth there.

’We’re small in the US, of course, but we’ve taken our customer service and convenience model there [TD is open long hours, including on Sundays]. We’ve had some fun and we’re very customer-oriented.’

This means that, despite the slowing of global markets and the negative environment generally, TD can still demonstrate a growth story. Its share price moved up from C$55 to C$93 ($56 to $95) over the seven years to April 2012 – and that’s in a strengthening currency market.

‘It’s very important for us to be out in the world talking about both Canada and TD Bank,’ says Sankovic. We want investors to say, Canada is different.’

And indeed it is: blessed with natural resources from potash to gold, and rather more common sense in the financial sector than many countries can boast, Canada’s economic story reads like a fairy tale compared with those of most of its counterparts in the western world.

Of course the downside of Canada’s relative economic strength is that to foreign investors – and TD is 35 percent US-owned, 10 percent European – valuations can look a bit toppy. So how does Sankovic counter this? ‘We say, Yes, but we have a brand with consistent earnings growth over the long term,’ he responds.

No alarms

It may not sound exciting but then we’ve all come to the conclusion that we’d prefer a bit less excitement from our banks post-crisis. Do TD’s investors and analysts also want something different from the bank’s IR? Have the conversations changed?

Sankovic says they have. ‘At meetings with individual investors, or with groups, or at conferences, the beginning is all about macro issues, whereas in the past it would have started off with TD-specific stuff,’ he notes. ‘This is certainly a change. IROs these days could do with a minor in economics. Everybody in IR has had to up his or her game.’

And how long does Sankovic envisage this lasting? ‘I think we’ll have more of the same until the US economy turns around, the US elections are over, the European issues have been sorted, and the Chinese economy has stopped slowing down,’ he says.

‘The macro factors are here to stay for the next five to 10 years, so we as an IR team have to accept being in a slow environment.’ Interestingly, to Sankovic that doesn’t seem to be a daunting prospect.