Louise Keeling talks to IR Magazine about investing below $1 bn and the benefits of founder ownership

In the year before Louise Keeling joined RWC Partners to head the long-only global equity team and launch the Global Horizon Fund, the London-based active fund manager snapped up Hermes’ Focus Asset Management – and posted record assets of $5.2 bn, up from $3.9 bn the previous year. Today, RWC has $7 bn in assets under management.

Prior to RWC, Keeling – who began her career as a graduate entrant at the Bank of England – spent six years at Marathon Asset Management after a spell as a US portfolio manager at Insight Investment. In September last year, RWC registered with the

SEC, which allowed it to move into the US market.

The fund manager, which was founded in 2000, says the key to its success is ‘the hiring and retention of some of the most talented fund managers in the investment industry’. In April 2013, Keeling – who describes her investment style as ‘long term and contrarian’ – joined that team.

|

'I don't spent much time focusing on the market cap - it's about whether there is value' |

What percentage of your assets under management is in equities?

The vast majority: 76 percent is in equities, the remainder in convertible bonds.

RWC has done well in the short time it has been established. To what do you attribute its success?

RWC has a very entrepreneurial culture. The fund managers have historically performed well and RWC attracts them into the company. RWC doesn’t try to cover every possible asset class, every possible fund. It launches funds where it believes it can excel by finding fund managers it believes can be the best in class in that area – that’s why there is a finite number of teams.

RWC has attracted individuals because there is a revenue share on the products, which means there’s a lot more skin in the game for the fund managers than at a more standard fund management operation – it really matters to them and RWC that the products perform. There’s a very strong alignment between the client, RWC and the investment teams.

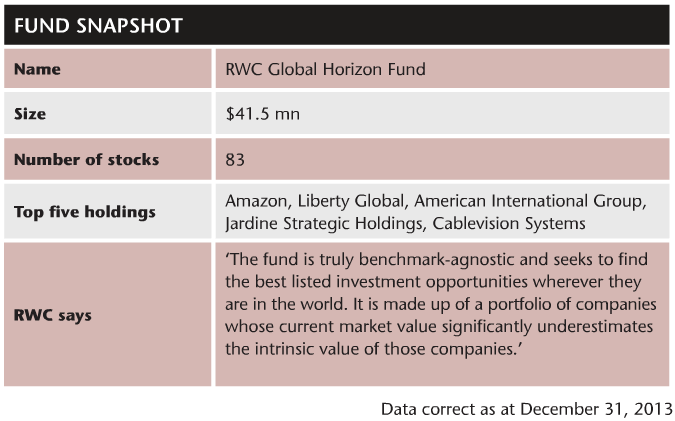

How did the launch of the Global Horizon Fund go?

It was launched at the end of November 2013 and there has been a lot of take-up from institutions, foundations and endowments,

so we are very lucky people have become engaged so quickly.

From some issuers’ perspective, RWC is a long/short house. What percentage of assets under management is long-only?

Ninety-two percent of our managed assets are long-only and 8 percent are long/short. The first fund RWC launched in 2000 was a long/short fund but the business developed from there and the majority of products are now in long-term equity and convertible bond strategies.

You focus on ‘capital cycles’. Can you explain this approach?

Capital coming out of an industry often means a very poor demand environment or excess capacity, so most people who are focused on performing between January 1 and December 31 will not be interested in those companies. But I have a different perspective: I don’t have to make huge predictions on the demand side. I focus on asking, Are these mispriced assets? and Is the bad demand environment priced in?

Often I can see a change in the supply side that means even if demand stays at current levels, returns are likely to improve because of what’s happening on the supply side. Supply is often far more visible than demand and translates directly into returns.

In effect, there’s a time arbitrage as most people’s time frames are much shorter (they can’t focus on the supply side; they have to focus on the demand side) so these less-popular, contrarian stocks are excessively discounted due to the myopia of most fund managers. I am an owner of firms, not a renter.

What’s your average holding period for a stock?

More than five years.

You also focus on ‘management incentives and alignment of shareholders’ interests’ – can you elaborate on that?

I think about the intrinsic value of a company. I think of the company as an owner would – as if I owned 100 percent of it. I think about the competitive environment and how it might change, how capacity is going to change over the next few years, the cash flow that company is going to produce, and that all builds into an intrinsic value for me.

Then I look at the market price and, if it is below the intrinsic value, that company is interesting to me. The reason management alignment matters is that the differential between the market price and the intrinsic value is more likely to be narrowed if capital is effectively allocated over time.

If you have a good management team thinking and acting like an owner, the possibility of that differential narrowing over time

is much greater. If management focuses just on sales growth at any cost – unprofitable sales – then it is very likely to be destroying value. If it is allocating capital in a creative manner, if it is value-focused, if it is thinking about free cash flow rather than earnings, that differential is going to narrow over time.

How would you describe your investment style?

Long-term and contrarian. The other part of the capital cycle is that you find companies with very good returns. People might assume returns are going to deteriorate over time but I may have reason to believe they won’t deteriorate at the rate the market is assuming.

One example is something like Amazon, where the firm shares a lot of its economies of scale with its customers, enabling it to build out the competitive moat, which I believe is sustainable. And because you’ve still got founder Jeff Bezos there, owning 19 percent, he is making significant investment in the company that hasn’t yet borne fruit but I believe will do; all those things mean it’s not fully baked into the valuation yet.

So I describe my approach as ‘contrarian’ even though things like Amazon might not be thought of as such. But I think about them in a different way from some, and I’m thinking over a longer time frame.

Any favored sectors?

It is on a stock-by-stock basis but there are a couple of sectors that are particularly interesting, one of which is cable. I have liked the cable industry for years and continue to do so as the capital intensity has peaked and you are beginning to see consolidation in the US and Europe, which bodes well for free cash flow generation in the future. This is particularly true if a more concentrated sector allows content-cost inflation to come under control.

Does a company have to be profitable before you invest?

Not necessarily. Something might be making losses because it’s at a trough in the cycle but once that excess capacity comes out, you may end up with a regional duopoly, making strong returns on investment, for example.

Do you have any current likes?

Amazon is a stock we like, and Spain is a region I like currently. There has been massive consolidation in the Spanish banking system. It’s probably not fully out of the woods on a provisioning basis but there is the new book of business, which is very profitable, and the change in that market suggests it is going to be more rational in the future than it has been historically – and it is still at a discount to book value.

The structural reforms that are currently taking place in Spain really are breathtaking, and they have set the country up really well for the next decade from a competitive standpoint.

What about dislikes?

Australia is very expensive but part of that is for structural reasons because the superannuation funds are continuous buyers of Australian stocks, so it looks very expensive on a global basis, especially Australian banks.

What’s your average market cap size for a holding?

I will go anywhere in the market cap range. What’s interesting is that you sometimes find good alignment of [management] interests at the mid-cap level [Keeling defines this as less than $1 bn] because the founder is still there or management is very focused on the business. But that doesn’t preclude me from owning mega-caps. For example, Amazon has very good alignment as Bezos is still there. At Zions, founder Harris Simmons is still there. TripAdvisor – the founder is still there.

Why will you invest below $1 bn?

I had Standard Pacific in 2011 and the market cap was $450 mn. I’ll go wherever the value is. I find it ridiculous that people say, I can’t buy it, it’s too small. Then the stock more than doubles to $1 bn and they buy it. That’s nonsense. I don’t spend much time focusing on the cap – it’s about whether there is value.

What’s your active share – that is, how much do your holdings differ from indexes?

My active share is 94 percent. I currently hold 83 stocks.

Where do you stand in terms of dividends vs buybacks?

I have a keen interest in any management team’s capital allocation decision-making process, and dividends and buybacks are a part of that. I like management being prudent with capital so redistributing capital to owners when it doesn’t need it for business opportunities is a positive. If management wants that cash back at a later stage, it can go to shareholders and ask for it again.

I am most interested, however, in understanding how a management team thinks about dividends and buybacks. Clearly when the company is massively undervalued by the market at any one point in time, there is a significant return benefit to the organization in buying back its shares while they are underpriced.

What I don’t like to see is management viewing buybacks as the same as dividends or a function of cash flow generation. Then you get into the situation that happened when investment banks ended up buying back stocks at the peak of cash flow generation and then raising equity at the bottom of the cycle. You end up with this haircut on returns to shareholders through the cycle because management has misallocated capital.

So what I want to understand is how management comes to the conclusion that its company is undervalued or overvalued. If it is overvalued, management should use dividends to redistribute capital back to shareholders.

Would a management team ever regard its stock as overvalued?

Potentially. It may not say as much to me directly in a meeting but it can signal that attitude by the fact that it is only doing dividends, if it historically thinks smartly about buybacks or if management members are selling their personal equity holdings.

Gill Newton is a partner at Phoenix-IR, an independent investor relations consulting firm