Management style at Japanese companies called into question

As falls from grace go, Toyota’s has been nothing short of catastrophic. Then again,

it had a fair way to fall. The Japanese car maker has long been an emblem of the Japanese success story, Toyota’s ubiquitous cars a symbol of the global dominance of Japanese industry. Now, several million product recalls later, Toyota’s reputation lies seriously damaged.

In an interview with IR magazine in 2007, Steven Curtis, corporate manager of investor relations,

said Toyota’s 295,000 employees were motivated by the concept of kaizen, an obsessive obligation to be

better. The Japanese preference for perfectionism has served Toyota well historically, yet the challenge it now faces comes from two other features associated with Japanese corporate culture: weak corporate

governance and a tendency to shelter senior

management in the face of adversity.

The firm, which has had an American depositary receipt program in the US since 1999, is not without its plaudits for IR: it won in 2007 and came fifth in 2008 behind TSMC in the category of best IR by an Asia-Pacific company in the US market at the IR Magazine US Awards. The Toyota US team consists of three communications professionals. Curtis, who heads up IR and communications, was unable to participate fully in this article due to ‘severe time constraints’: Toyota’s

management had been testifying to Congress the previous week.

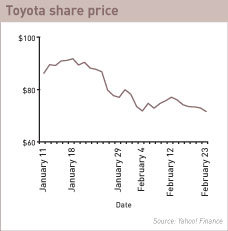

Testing times Toyota’s devastating product recalls have tested communications to the limit. By February 10 the company’s share price had dipped by nearly 20 percent in

less than four weeks, despite

the announcement of improved guidance the previous week, as investors engaged in worst-case scenario planning about the scale of the manufacturer’s woes (see Toyota share price, right).

Toyota’s devastating product recalls have tested communications to the limit. By February 10 the company’s share price had dipped by nearly 20 percent in

less than four weeks, despite

the announcement of improved guidance the previous week, as investors engaged in worst-case scenario planning about the scale of the manufacturer’s woes (see Toyota share price, right).

Many said the manufacturer waited too long to reassure the market. ‘Speed is of the essence in any crisis and investors want

to know what the financial implications are,’ says Adrian Rusling, partner at Phoenix-IR. ‘Toyota did a lot subsequently to remedy the situation but the initial lack of communication around the recalls harmed its reputation badly.’

‘You have to address – from an IR perspective – that the market overreacts anyway and you must provide hard facts: the sell side wants numbers, the buy side wants to be reassured management is in control,’ adds Anne Guimard, a former sell-side analyst and founder of FINEO,

an IR agency in Paris. ‘You need

an integrated IR and PR action plan. Corporate communications, internal communications, IR and marketing must work together. Companies in crisis should provide FAQs, press releases and conference calls at the highest level.’

Guimard points to previous recalls and their effect on the capital markets. ‘There is a lot of historical

evidence suggesting that such types of event trigger more negative press and perception than actual cost – as was the case with Firestone Tires,’ she explains. ‘So any company that could be vulnerable to a product recall needs to prepare thoroughly.’

An academic study into the Firestone Tires recall in 2001 found ‘initial loss in the market value, both

for the Bridgestone Corporation and Ford Motor Company, was far in excess of direct costs associated with recall.’ The researchers found that market losses are approximately equal to the near worst-case

estimates of direct and indirect costs, litigation costs, regulation compliance costs and costs associated

with future losses in sales.

Richard Wolff, managing partner for North America at Kreab Gavin Anderson, also contends that the overreaction is attributable to worst-case-scenario forecasting from the sell side. ‘Toyota’s stock

declined by almost 20 percent from a high of $91.78

in mid-January, yet the company, in the midst of it all, announced improved guidance – with no appreciable upside effect on the stock price,’ he says. ‘It seems

to me that worst-case modeling was driving this.’

Keep it real

Rather than engaging in worst-case scenario

planning, Wolff advises providing realistic case

scenarios for analysts. ‘A company can’t simply assume the general information about the recall, largely given through the media, is sufficient,’ he points out. ‘This is also true with respect to direct information delivered to Congress or the administration. This information needs to be reiterated and targeted to the investment community to ensure its full

understanding, and to help the Street accurately gauge the impact of the recall on the company.’

The debacle has been described as a PR disaster but Jamie Allen, secretary general of the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA), suggests the problems are more systemic. ‘It can’t be just PR – it must run deeper,’ he argues. Allen points out that Toyota has always been openly opposed to modern, western corporate governance practices. ‘The firm has traditionally been a well-managed company with good levels of disclosure but it has always maintained a policy of not having independent directors and audit committees,’ he explains. ‘It does have an advisory board but no international members sit on it. There

is value in having diverse opinion yet Toyota has always maintained a policy of not having independent directors on its board.’

In 2008 ACGA produced a white paper on corporate governance in Japan, drawing on the experience of institutional investors and analysts in the country. Major failings included the lack of independence, accountability and shareholder rights but there were also problems with poison pills and inconsistent preemption rights. Non-domestic shareholders have often complained that it is difficult for investors to hold management to account in Japan. Domestically, shareholder engagement remains limited. The largest Japanese pension funds and asset managers use their voting rights but prefer to remain silent when

it comes to making policy statements.

The traditional contention that Japanese firms are strong at communicating with stakeholders rather than shareholders has also been called into question. ‘The argument that economies such as Japan and Germany are driven by stakeholder relations rather than shareholder relations is a massive oversimplification,’ notes Allen. ‘When something like this happens, they should be very sophisticated in their communication but that has not proven to be the case.’

Resistance to change

Toyota’s reluctance to embrace internal checks and balances has, in effect, stifled the development of new ideas in Japanese corporate thinking. ‘It has actively opposed some of these corporate governance ideas to the extent that it has limited the spread of governance ideas in Japan,’ says Allen. ‘If Toyota doesn’t do it, that gives other Japanese companies

a reason not to do it.’

There are many ironies to this depressing chapter in Toyota’s history, but there are also many lessons. The need for rigorous crisis planning cannot be underestimated, nor can the

need for a forthcoming approach from senior management.

Investors and consumers need guidance. There is a great deal

of empirical evidence that points to the overreaction of the capital markets in times of crisis and

the Toyota example serves only

to underline this.

What remains less certain is whether attitudes to corporate governance in Japan will undergo any changes as a result. ‘The

conclusion one would love to

jump to is that Japan will be more open-minded about more non-

Japanese corporate governance ideas,’ says Allen. ‘The situation certainly challenges the debate

that favors the efficacy of traditional Japanese governance standards. It is unclear, however, whether it will affect practices at other Japanese companies in the future.’