Index funds and ETFs are accounting for an increasingly larger share of the equity market

Over the summer, news emerged that CalPERS plans to review its use of external active equity managers. In the ongoing debate between advocates of active and passive investing, that made quite an impact. After all, CalPERS manages more than $250 bn in assets, making it the largest public pension fund in the US.

CalPERS’ investment committee will use index strategies wherever it lacks ‘conviction’ that active managers can add value, Pensions & Investments reported. It will also closely monitor the performance of individual active managers during 2014, noted the publication, quoting Eric Baggesen, CalPERS’ senior investment officer of asset allocation.

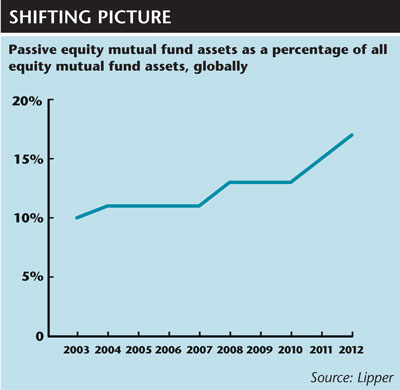

The story highlights the continuing shift away from active asset management and toward passive investing. Passive funds now account for 17 percent of worldwide equity mutual fund assets, according to data from Lipper; 10 years ago, that figure stood at 10 percent. In the US the figure is slightly higher, with passive funds today making up 21 percent of the market. Demand for exchange-traded funds (ETFs), meanwhile, continues to grow swiftly: iShares expects ETF assets in the US to jump from $1.5 bn to more than $3.5 bn in 2018. BlackRock, the owner of iShares, said earlier this year it is still ‘early days’ for ETF adoption.

For companies, the market is evolving at a rapid pace, adding to the complexity of knowing who owns you, who trades you and who you should target. Still, a number of IROs and consultants argue that the rise of passive investing has had little impact on the fundamental aspects of the IR role.

Lift off

Looking back, Richard Davies, founder and managing director of RD:IR, the London-based IR company, recalls how passive investing first took off in a big way at the end of the last century. ‘Passive investing grew steadily during the late 1990s and early 2000s in terms of the rise of indexation, by both UK and international investors,’ he explains. ‘We also saw a significant rise in quant investment during that period, which, while not strictly a type of passive investment style, was a move away from the traditional active management approach.’

Closet indexing rose during this period, too, says Davies, driven by a greater emphasis on performance by beneficial owners, who were partly influenced by the stellar returns of hedge funds at the time. ‘In the latter half of the 2000s, we saw the rise of ETFs as an asset class to a significant degree, including as holders of equities, which further increased the quantum of stock held on an indexed basis, either on a long or synthetic basis,’ he notes.

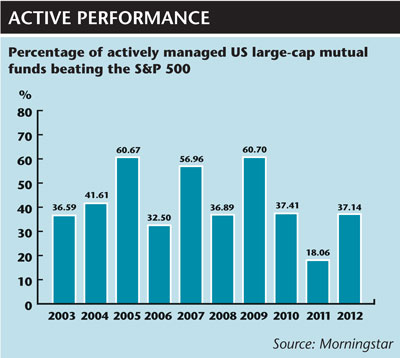

While product innovation has helped fire the passive boom, so has growing scrutiny on the performance of active managers. While a few beat the market consistently, numerous studies have shown that the majority fail to outperform on a regular basis. Investors have wondered, understandably, why they should pay active fees for what will most likely be below-par performance.

Recent research by consumer finance website NerdWallet, for example, finds that only 24 percent of active managers in the US beat their benchmark over the last decade. The study reports that active managers actually generated slightly better returns than index managers, but their higher fees meant stock pickers returned 0.8 percent less on average.

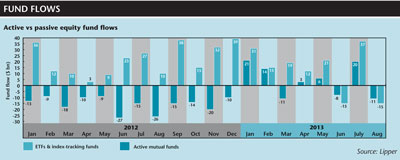

These factors helped ETFs and index-tracking funds to secure far superior asset flows compared with active mutual funds during 2012, according to global data from Lipper. Last year every month saw net inflows for the former and net outflows for the latter. The picture has been more mixed in 2013, though ETFs and index funds had still accumulated $71.2 bn more in net assets by the end of August.

Click for a larger image

Blurred lines

A complicating factor is the blurring of the lines between what constitutes active investment and what constitutes passive. Scottish Widows Investment Partnership (SWIP) today employs strategies including ‘enhanced passive’, which follows a quantitative approach but aims to outperform the benchmark by 0.5 percent over three years.

‘There is a real blend of active and passive within some of the same funds,’ explains James Tickner, head of global investor targeting at NASDAQ OMX Corporate Solutions. ‘So the lines have also broken down a bit and there is not quite the black-and-white distinction there used to be.’

In addition, some investment firms commonly perceived as passive may be actively involved in areas such as corporate governance. A case in point, says Tickner, is UK insurer Legal & General, which regularly does meetings with companies – particularly with chairmen – from a governance standpoint.

‘By not engaging with that investor on that level, there is potentially some damage to be done in terms of L&G’s equity stake,’ he explains. ‘You can’t necessarily take those index positions for granted. Be prepared to engage with… the real behemoths of index management. Be ready to have that dialogue with them should the time come.’

With low-cost alternatives on offer, it has often been the active managers that don’t stray far from their benchmark that come under the most pressure. SWIP’s change in tack came from a belief there should be a greater distinction between higher-cost, active strategies and lower-cost, passive ones.

Tickner predicts still more squeezing of active managers that continue to stick close to their index weightings. ‘I think it is very possible the market will polarize a bit more,’ he observes. ‘The strategies that aren’t really one thing or another will seriously struggle and, to demand those active management fees in the future, companies are going to have to demonstrate some real outperformance.’

Stay active

While the amount of passively managed assets has grown, Davies warns against thinking less outreach is required from IR teams. ‘The rise of passive investing has had little impact on the work of IR teams other than making it even more important that they understand the nature of their investor base in terms of investment objective and deal with investors appropriately,’ he states. ‘Even passive investors require company information on a regular and thorough basis, particularly on the corporate governance side, where their non-active trading strategies make understanding the corporate governance model of the company even more important.’

Tickner agrees that the diminishing size of the active investment market requires IROs to pay even closer attention to the specific objectives of the investment firms and funds they are meeting with. ‘The competition for capital among those active managers that can be influenced by an IR person has become fiercer than ever,’ he says. ‘[There is a] need, consequently, for companies to really understand the funds they are meeting with. What is the fund’s benchmark? Is it a UK company meeting a fund that is benchmarked against the S&P 500, for instance? What is the track record of investing outside of the benchmark?’

Tickner adds that companies should be mindful of index-huggers. ‘Even some of the funds that do meet companies are quasi-passive investors… they don’t deviate too far from their benchmark,’ he explains. ‘So again the consequences for companies are to really understand who they are meeting with: how active is your active manager?’

Critical to understand

One IRO keeping a close eye on passively managed asset growth is Kate Scolnick, vice president of IR at Seagate Technology, the data storage firm. She is analyzing its impact on her stock’s price and volume.

‘Considering that the largest portion of the equity markets’ trading volume on a daily basis is index and ETF-driven, it’s becoming critical for IROs to understand how these elements are affecting market conditions and their company’s stock,’ she says. ‘From a communications perspective, index and ETF trading volumes can cause significant trading volatility around corporate news because these products are designed to exploit inefficiencies.’

Scolnick uses a combination of trading analytics and stock surveillance analysis to monitor volume connected with both passive and active funds. ‘By understanding the delta between where passive and active pricing is being set, I get a general sense of whether the current stock price is trading at a ‘rational’ or broadly supported price,’ she states. ‘If the delta between these two forces widens, it can mean there is a potential price correction coming, particularly if it happens during option expirations or ahead of an earnings report.’

She is supported in her work by ModernIR, an IR firm focused on understanding today’s market structure run by Tim Quast, himself a former IRO. ‘Rational money may only set the price about once a month in our client base,’ he says. ‘Nineteen out of the 20 [days] that remain, indexes, ETFs or fast money are responsible, because they are constantly rebalancing, shuffling and trading around positions.

‘That behavior is dominating: it’s driving a substantial amount of volume, it’s setting price frequently and it’s creating divergences from fair value. I think the IR folks who quantify it and sort it out are probably doing the kind of things you need to do today.’

Other IR professionals, however, say the uptick in passively held assets has not really changed their day job. For example, Jack Carsky, head of IR at Visa, says it ‘hasn’t had much of a direct impact, except when we get added to indexes.’ Visa joined the Dow Jones this September in a reshuffle that saw the familiar names of Bank of America, Hewlett-Packard and Alcoa all dropped. It’s also just three years since Standard & Poor’s added Visa to the S&P 500.

‘We play a formative position in certain ETFs,’ says Carsky. ‘But if you look at Spiders [an ETF based on the S&P 500], for example, the amount of Visa shares inside is not that many. The way these funds are structured means they are not required to have a ton of stock inside them, so they don’t take a lot of shares out of circulation – whereas index funds obviously do.’

If anything, the accumulation of assets in passive funds has been marginally positive, says Carsky. ‘With a firm our size, given the float, liquidity and everything, it’s usually net beneficial in terms of having less supply at a given point of demand,’ he says. ‘I’ve never been able to correlate an increase in the amount of money in index funds with daily trading.’

Small benefits

For smaller companies, there may be benefits from the growth of ETFs, according to a research report from Ipreo, the market intelligence firm, released earlier this year. ‘I don’t think the expansion of ETFs has a huge impact on large caps,’ says Brian Matt, director of data strategy and analytics for Ipreo, and one of the report’s authors. ‘But if you think about it, any assets flowing into ETFs tracking small caps will have ancillary benefits for the company in terms of increasing liquidity, both in the immediate shares traded by the AP [the authorized participant that buys shares on behalf of ETF sponsors] and in the shares loaned out from stable ETF positions to short-sellers.’

This increased liquidity could open the door to active managers at larger investment firms, notes Matt. ‘Liquidity is the lifeblood of institutional investment in small caps, and anything that boosts liquidity can allow a manager to take a more significant position without hitting risk-management limits,’ he explains. ‘Down the road, small-cap IROs may have an easier time marketing themselves to larger names that are prevented from taking stakes in illiquid firms if ETF holdings are generating more liquidity.’

With the growth of passive investing set to continue, what other consequences might there be over the coming years? Ipreo’s research notes that, if regulators don’t intervene, one day ETFs could be among the largest institutional investors on company registers. Given that the three largest ETF managers – iShares, State Street Global Advisors and Vanguard – typically do not engage with companies over corporate governance, this could be a ‘positive trend’ for corporate secretaries, the report notes. Ipreo points out, however, that ultimately this may lead to more power in the hands of proxy advisory firms.

For Tickner, another implication could be greater demands for investor access from the active managers that remain. ‘We have already seen a trend over the last few years in demand for divisional director access from the buy side increasing, and that seems likely to continue,’ he says. ‘The stock pickers’ focus will be to understand more about the qualitative aspects of a business such as management strength and vision, which quant models alone struggle to account for.’

Time for a comeback?

Of course, active investment management is not on the way out entirely. Indeed, some advisers are predicting a comeback – if not a dramatic one – for stock picking. Kevin Malone, president of Greenrock Research, recently told InvestmentNews that, given the expectations for slow equity market growth over the next few years, investors should become more discerning about their stock selections.

Active management performance also tends to be cyclical. While 2011 saw less than 20 percent of US large-cap active managers beat the S&P 500, periods of weak returns are often followed by years where the majority outperform, according to research from Morningstar – so a broad uptick in returns for active managers could help taper the flow of assets to index funds and ETFs.

For Carsky, the number of Visa shares in passive products would need to ‘double or triple’ before he expects any significant impact on his work – a situation he says he can’t see happening overnight. ‘The beauty of humanity is that every individual always thinks he or she can best an average – otherwise money management wouldn’t exist,’ he concludes.