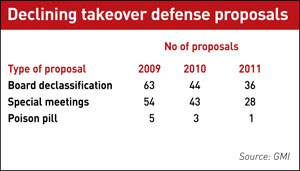

Statistics suggest companies are relying less on poison pills and other takeover defenses, reports Aarti Maharaj

A new report indicates that shareholder activists have enjoyed some success in dissuading US companies from employing certain takeover defenses that may undermine shareholder rights.

The report, entitled ‘Proxy season wrap-up: successful activism dismantles takeover defenses’, released by GovernanceMetrics International (GMI), indicates a continuing reduction in the use of all kinds of takeover defenses, certainly among more high-profile large-cap US companies. Smaller caps generally take a little longer to adapt to the new governance mores, if only because they are less often engaged by activists or pounced on by the press.

The reduction in takeover defense proposals appearing on proxy statements is probably driven by a number of factors, according to Beth Young, senior research associate at GMI and author of the report. ‘In addition to successful shareholder activism, companies may be more willing to settle takeover defense proposals rather than allow them to appear on the proxy statement,’ she says.

Alas, there is no way to track this accurately, because proponents submit their proposals direct to companies without the need to file anything or meet any regulatory requirements. As GMI points out, ‘We do not have the data needed to say with certainty that companies are taking a less hard-line approach.’ But it seems a reasonable supposition.

Far-reaching consequences

Sanjay Shirodkar, of counsel at DLA Piper’s public company and corporate governance practice in Baltimore, says there has been a marked increase in the number of ‘hostile’ approaches made since the beginning of 2010.

‘The potential dismantling of a company’s takeover defenses is an issue that can have a serious impact on its long-term success,’ Shirodkar explains. ‘Such decisions merit thoughtful and thorough analysis of many different issues and are best undertaken with the assistance of advisers.’

Nevertheless, he accepts the trend. ‘Over the course of the past 10 years or so, poison pills and other takeover defenses have come under increasing scrutiny, and many large-cap companies have reassessed their takeover defenses,’ he notes.

A key finding from the report is that only one third of US boards are now classified, which is the lowest level since GMI started tracking such data. As a result, corporate directors now serve terms typically lasting between one and eight years.

‘Boards may feel uncomfortable being too far outside governance norms so, as more companies declassify, pressure increases on the holdouts to follow suit,’ the report explains. ‘More personally, directors may also wish to avoid facing withhold/against voting recommendations by proxy advisers.’

Shirodkar compares this finding to his own review of annual meetings over the past year. ‘Based upon information we have reviewed for annual meetings scheduled between June 30, 2010 and June 23, 2011, we believe that more than 50 companies have faced shareholder proposals to eliminate their classified boards,’ he says.

The report’s overview of trends in shareholder proposals also notes that the number of proposals asking companies to give shareholders the right to call special meetings has nearly halved, dropping from 54 in 2009 to 28 this year. And the proportion of S&P 500 corporations whose shareholders don’t have the right to call a special meeting is now less than half, at 49.6 percent. That’s an all-time low.

As for poison pills, these have gone right out of style. There were just five at S&P 500 companies in 2009; now there is only one. Indeed, the number of poison pills used to discourage hostile takeovers declined to just over 16 percent of firms last year. That’s a significant reduction since 2002 when more than half of US companies still used this technique.

Written consent surge

On a separate issue, GMI acknowledges that shareholders have found a new channel for their activist energy. This is on the question of action by written consent, rather than a meeting.

Because of the novelty of this, there is no comparative data but so far this year shareholders have voted on 32 proposals on the subject. And there are plenty of vulnerable companies: at more than 60 percent of Russell 1000 companies, shareholders either are not allowed to act by written consent or they have to have backing from 100 percent of all shareholders, making success pretty much impossible.

GMI says its data on proponents suggest that the mostly individual shareholders who put forward special meetings proposals are the same ones as those now behind the written consent proposals. Backing is higher, however, given that many institutions’ voting guidelines support this issue on an across-the-board basis, obviating the need to consider proposals case by case.

So US companies should take heed: the reductions in proposals outlined in the GMI report may well give way to an increase in written consent proposals that are cheaper to effect, because they require little customization for different companies. They’re also easier to get passed.

This article appeared in the August print edition of IR magazine.