Demystifying the secret world of algorithmic trading

Remember the old days? ‘Bigfoot in Boston is making the moves,’ your exchange contact might have whispered. Over the next few days or even weeks, you could watch as a large institution’s position was leisurely built up or unwound. Here’s how it happens today: blink and you’ve missed it.

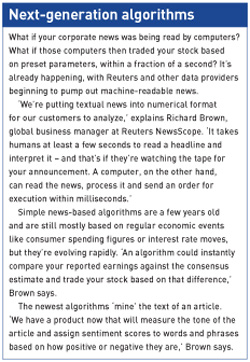

Algorithmic trading is estimated to account for a third of all equity trades in the US and is predicted to make up more than half of trading volume by 2010. Hedge funds were behind the first surge but now, with Reg NMS in the US and MiFID in Europe spawning ever more electronic communications networks (ECNs), or dark pools, to trade in, mainstream investors are getting in on the act. Last year the NYSE’s new hybrid electronic market boosted algorithmic trading, as did the London Stock Exchange’s new electronic system, launched in June 2007. There are two main categories of algorithms. New alpha-generation or news-based models are based on information from analysts or machine-readable news feeds like the ones Reuters and Dow Jones have started producing. These have only just begun to take hold (see Next-generation algorithms, right). Execution or order-handling algorithms were first developed around 15 years ago and have exploded in popularity during the past five.

There are two main categories of algorithms. New alpha-generation or news-based models are based on information from analysts or machine-readable news feeds like the ones Reuters and Dow Jones have started producing. These have only just begun to take hold (see Next-generation algorithms, right). Execution or order-handling algorithms were first developed around 15 years ago and have exploded in popularity during the past five.

Guy Cirillo, global channel sales manager for advanced execution services at Credit Suisse, describes these algorithms as ‘mimicking what humans used to do before computers were in the middle.’ Traditionally a buy-side investor would call up a broker’s cash desk and place an order, then a trader would execute the order all at once or bit by bit, often over days. Now the order gets sent to the broker electronically. If it’s a large block, and the broker has trading algorithms set up for that account, the order may get split into hundreds of small executions.

On any given day, 75 percent to 80 percent of Credit Suisse trades are executed using algorithms, and 51 percent occur in dark pools. ‘We’re hitting every single liquidity point out there, not only in the US but globally,’ Cirillo says. ‘We can hit over 40 dark pools in under a second, achieving best execution. It’s an advantage to our clients, but it should also be considered an advantage to issuers.’

Hidden strength

Algorithmic trading’s main goal is to avoid market impact by spreading the trade around and keeping large investors anonymous. ‘Investors always want to remain anonymous, but the system never really allowed it because there were so many leaks,’ says Marc Greene, head of Ipreo’s global markets intelligence group.

The big question for IROs is how algorithmic trading affects the character and transparency of their stock’s trading. According to Cirillo, today’s average trade is under 300 shares; five years ago it was thousands. ‘Algorithms create a less volatile environment, especially for illiquid stocks,’ he says.

But Sajid Daudi, head of surveillance at Ilios Partners, says algorithmic trading actually increases short-term volatility. ‘There’s definitely a market dynamic shift happening,’ he comments. ‘Institutional investors are going to ECNs because they can get better pricing, and the big quant traders are the more aggressive day-traders, which affect day-to-day volume. The end result is increased volatility.’

All that volatility makes some of Ilios’ clients agitated, Daudi admits, with a lot of intraday moves going unexplained. But traditional stock surveillance, which tracks custodial accounts where trades are settled, is immune. ‘In terms of behind-the-scenes settlement, we see all the separate trades consolidated under the beneficial owner’s name,’ Daudi notes. ‘It doesn’t matter where the trades are executed.’