Emphasis on fixed income to increase as company demand for equity investment is projected to outstrip supply

Anyone who studies the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis understands the power of bond investors to bring governments to their knees.

But CFOs and their IR teams must also get to grips with the ability of debt markets to topple companies. Even directors of companies with intelligent strategies and sound finances must feed debt fund managers information.

Georg Grodzki, head of credit research at Legal & General Investment Management, says even companies with low leverage need access to debt markets of reasonable size at affordable terms, despite tough times.

They must communicate regularly with investors and have consistent financial policies to create conditions in which debt investors are confident in them. If they fail, most companies will incur significant refinancing risks.

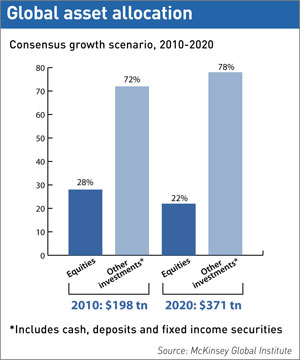

What’s more, the importance of debt IR is set to grow. Global companies’ demand for equity capital may outstrip supply by $12.3 tn by 2020 as investors avoid stocks, spurring firms to take on more debt, warns McKinsey & Co in a report published last December called ‘The emerging equity gap’.

Mind the (equity) gapSeveral forces are reducing the role of listed equities, according to ‘The emerging equity gap’, a report published by McKinsey & Co last December. The most significant is transfer of wealth to developing nations: private investors in the developing world put less than 15 percent of their portfolios into equities, while the figure in developed nations is 30 percent-40 percent.Meanwhile, the demand for equities in developed markets is expected to fall as a result of ‘aging, shifting pension regimes, growth of alternative investments and new financial regulations,’ notes McKinsey. |

So what insights on debt should IROs give to fund managers? John Hamilton, manager of the Jupiter Corporate Bond Fund, says the bondholder looks at companies for creditworthiness, unlike shareholders who want the ability to increase earnings per share (EPS).

‘We are interested in the company’s attitude to improving the credit rating, whether or not we agree with Moody’s,’ he explains.

The group’s structure is also a potential source of risk if intra-group transfers of cash undermine the debt investors’ claims and favor shareholders, says Hamilton.

‘Do they issue bonds from a subsidiary, then upstream cash to a group that pays dividends?’ he asks. Then there is subordination risk: the company must satisfy shareholders, banks and bondholders, Hamilton adds. ‘If the firm refinances the bank debt, we should know on what terms, as much as that is legally possible,’ he says.

Consistent conversation

How are the conversations with debt investors different from those with equity investors? Strictly speaking, there should be no difference, says Grodzki: companies should give the same strategic message to debt and equity holders, rather than tailoring their story to either group’s perceived expectations. ‘Consistency is key,’ he points out.

Hamilton agrees about consistency in relation to the sale of good subsidiaries, and adds that the more indebted a company, the more important EPS can become for bondholders as well as shareholders.

For example, a high-yield company is likely to have a business plan that commits it to growing its way out of debt.

Hamilton believes, however, that there are nuances when it comes to bond value versus equity value. He cites one contemporary difference between the conversations with debt investors and shareholders:

‘There are things that are good for bondholders and bad for shareholders, and vice versa. For example, a rights issue means that if a company goes wrong, there’s a larger cushion of risk capital before you hit bondholders. But if a company does a share buyback, there’s a smaller cushion, and it may use cash on the balance sheet.’

Another difference relates to banks, which are giving investors in their covered bonds a prior claim on a company’s earnings, compared with senior unsecured bondholders.

‘Shareholders are the most unsubordinated investors, so they don’t care as long as it is neutral for EPS and doesn’t undermine the company,’ says Hamilton.

So what should IROs do in practice? Grodzki says they should provide regular information about financial performance and targets, and should meet major investors at least once a year, whether or not they plan to issue debt.

That includes unquoted companies, which are quite big issuers of bonds, adds Hamilton. ‘Keep the conversation going,’ he says.

Getting there

Some companies are making progress. Visit the IR site of John Deere, the US tractor manufacturer, and you will find ratings by Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and a third agency, Dominion Bond Service, on the firm’s senior long-term and short-term debt, as well as outlooks.

Imperial Oil, the Canadian petroleum firm, mentions in its 2010 annual report its AAA rating from Standard & Poor’s and says it is the only Canadian industrial company to have this rating at the time.

Companies should also communicate with investors about debt denominated in foreign currencies. CNOOC, the NYSE and Hang Seng-listed producer of oil and gas, says in its 2010 annual report that its debt repayment will fall because all of the group’s debts are denominated in US dollars, which at the time had weakened against the renminbi.

Interest rate risk is another factor for investors, and CNOOC says fixed interest rates could reduce the volatility of funding costs in uncertain environments. It reports that 25 percent of its debts are fixed, and gives details about the term of its average balance.

What about relations with colleagues in treasury teams? Grodzki says IROs should bring staff from the treasury department to meetings as often as possible. Hamilton adds:

‘When you have roadshows, sometimes you get the chief executive and the treasurer, if it’s a smallish company. They want to show goodwill.’

Pension risk

Of course, investor relations teams must inform debt investors about all their liabilities, which includes not just bonds and loans but also any pension scheme deficit, notes John Ralfe, a UK-based independent pensions consultant.

Directors, after all, must pay cash to the trustees of defined benefit pension schemes that are in deficit. Share option schemes must be properly expensed and leasing by a retailer must be included, says Ralfe, a former head of corporate finance at pharmacy and healthcare products company Boots.

Ralfe – who has written about US pension schemes and carried out research for Royal Bank of Canada – also says IR teams should make sure debt markets appreciate the ways in which their companies have insured against risk.

For example, if pension scheme trustees have sold equities and reinvested the proceeds in the most secure bonds, that exposes investors to smaller dangers than if the pension fund had invested heavily in stocks.

Other ways to fight dangers include selling pension liabilities to insurers and paying investment banks to bring in hedging strategies.

‘Investors understand currency exposure, or an airline’s fuel exposure, but they don’t understand pensions risk in detail,’ says Ralfe. ‘Tell the market if you have taken that risk off the table.’