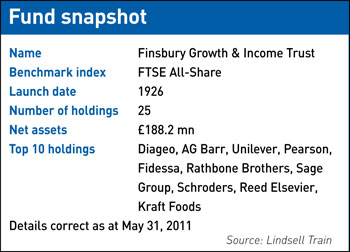

Alex Jolliffe talks to Nick Train, manager of Finsbury Growth & Income Trust

Nick Train is the fund manager of Finsbury Growth & Income. His positions are of interest because of his experience – he began his career in 1981 – and because of his returns.

Finsbury Growth & Income is one of just 12 percent of 531 UK investment trusts that have had the same investment adviser for 10 years or more. A shareholder who invested £100 ($164) in Finsbury Growth & Income 10 years ago would have £234.90 ($385) today, compared with the UK growth & income sector average of £183.90.

What are you betting the farm on?

Consumer goods companies, because investors have overreacted to fears about commodity prices. I have invested 39.1 percent of the fund in consumer goods groups, compared with 11.1 percent in the FTSE All-Share Index, our benchmark.

Investors are cautious about consumer staples companies such as Diageo and Unilever. They warn of pressure on margins from rising commodity prices such as energy and metals. The major consumer goods groups have acknowledged this: they admit they are unlikely to mitigate it by increasing the price of their brands when consumers are cutting back in many countries. But the bears are forgetting an important question: why are commodity prices rising?

They are going up because of new demand for the consumer staples that companies such as Diageo and Unilever produce: beer, fine spirits, soap, deodorants and ice cream. How can it be a seriously bad thing that hundreds of millions of consumers are expressing a desire to enjoy these brands? Diageo’s earnings will compound relentlessly as it sells more Guinness in Africa and more Johnnie Walker in Asia.

So what’s the bullish case for Unilever?

It wins a higher proportion of its sales in emerging markets than any rival – more than 50 percent, in fact. The group aims to double its revenues during the coming decade and it wants to increase its emerging market share from 50 percent to 70 percent.

What about the valuation?

Unilever has just sold its Sanex brand to Colgate for 3.6 times annual sales. But investors value the rest of the group at just 1.5 times sales, despite its growth potential – remember that half of the revenues come from emerging markets. From a strategic perspective, that’s pretty cheap. The 3.7 percent dividend yield and dividend growth pay us to wait while Unilever’s value is unlocked.

How have investors unlocked the group’s value in the past?

Unilever’s shares have quintupled over the last 20 years and have handsomely beaten the FTSE All-Share, which trebled. But Unilever’s dividend has more than sextupled – so its shares were behind the dividend growth. We expect the next 20 years to be even more ‘bagtastic’ (baggers are stocks that double, or better).

What are the significant risks for consumer goods groups?

The biggest one for Unilever is the long-term commoditization of consumer brands. If we look back over 100 years, a major proportion of our grandparents’ brands have become commodities. Competition from own-label manufacturers supplying supermarkets has commoditized soap powder, sugar and margarine. If Unilever were complacent and did not invest, the equity would be at risk.

What else are you betting heavily on?

Technology and the internet. We think the internet is in the same situation as Britain’s railways in 1855. In the 1840s, there was an enormous speculative bubble; after it burst, lots of investors lost their shirts. Not many years later, however, the economic benefits became very apparent.

And how is the internet now similar to the UK’s railways in 1855?

We had a huge boom in 1997-2000, then a collapse from 2000 to 2003. Investors think: it’s over. But in every aspect of working and private lives, the internet is more material.

So which stocks are you betting on?

I’ve had 5.1 percent in Sage, the business software group with a significant online operation. It is valued as if were a low-growth engineering company but it has high margins and wonderful cash generation. I have 6.1 percent in Fidessa, which provides trading and information systems to investors. It has become an increasingly indispensable part of the world’s capital markets.

How does the internet theme apply to media stocks?

News and entertainment were provided for free, so the economics of newspapers were ripped apart. But I am excited by the growth in the web assets of Daily Mail and General Trust (DMGT), especially MailOnline. It’s growing fast in the US and India. In the first quarter of this year, AOL bought US gossip website the Huffington Post. If we extrapolate from the very fancy price paid by AOL, there are hundreds of millions of pounds in unrecognized value in DMGT.

You have no oil and gas stocks. Are you concerned about forecasts of a peak in oil production?

The science of peak oil is unproven. But the task for BP and Shell is many times harder in the 21st century than the 20th. We didn’t hold BP because we thought it probably had to take more political risk in Russia to replenish its reserves.

This article appeared in the August print edition of IR magazine.