Two cases raise questions about when companies should be required to make a statement about bid speculation

The UK’s Takeover Code has come under scrutiny in recent months over when companies should be forced to confirm a bid. Under the code – which is policed by the Takeover Panel – companies must make a statement if news of an approach leaks and there is an ‘untoward’ movement in the share price. This responsibility rests initially with the bidder and then passes to the target once an offer has been made.

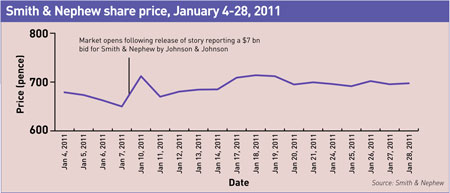

Two recent incidents, however, have raised questions about how these rules are being applied. The most recent situation involved Smith & Nephew, the UK-based manufacturer of replacement hips and other medical devices. In January this year, Sky News reported that Smith & Nephew had been approached before Christmas with a $7 bn bid from Johnson & Johnson. The following Monday, Smith & Nephew’s shares rose more than 10 percent, but the company would neither confirm nor deny the story.

Given the share price movement, it seemed likely either the alleged bidder or the target would be forced to say something to bring clarity to the market. No one said anything about the bid, however. Speaking at a healthcare conference that Monday, Smith & Nephew’s chief executive Dave Illingworth said the company would not be making any comment on market rumors, adding: ‘We clearly understand what our responsibilities are under the listing guidelines in the UK.’

So why didn’t Smith & Nephew have to make a statement? One reason could be that the bid was no longer considered live. Under the Takeover Code, if a company has rebuffed a bidder and does not expect it to return with an improved offer, it can consider the matter closed – in which case no statement is required.

Vital signs

There is no clear-cut test for determining whether a bid is still live, however. In each circumstance, this will be decided by consultation between the Takeover Panel and the company involved. ‘Most of the time – and I’ve worked on a couple of hundred of these things – you know whether it’s still going on or not,’ comments Philip Broke, a partner at law firm White & Case. ‘It’s not always clear, though. Occasionally the target will say no to the bidder but leave the door open for it to come back with a higher price.’

It’s safe to assume a formal offer was not on the table in the case of Smith & Nephew, according to another London-based M&A lawyer. If there had been an approach and there were ongoing discussions about a possible offer, then the target company would have been forced to disclose this through a stock market announcement, he explains.

Later that week in January, Smith & Nephew did make a statement, but the company was at pains to point out that it was not under any regulatory obligation to do so. This announcement came on Thursday, four days after the share price spike brought on by the Sky News story. The statement said Smith & Nephew was not in any discussions that could lead to a merger or takeover and made no reference to any other company.

Publish and be damned

The second incident that caused confusion about the code took place toward the end of 2010, when De La Rue, a bank note printer, rejected an approach from French rival Oberthur but didn’t let the market know. Over the following month, De La Rue’s shares rose 15 percent, which could have triggered a statement: according to the code, an ‘untoward’ movement in the share price comprises either 5 percent in a day or 10 percent following the initiation of a bid.

But companies can, in some cases, avoid making a statement if the movement can be explained by factors other than the bid approach. During discussions between a company’s advisers and the panel, the advisers may suggest other reasons that could explain the share price movement. These reasons could include positive sentiment about the sector in general or a rise in the overall stock market.

‘I’ve been in a situation advising a bidder, where we hadn’t approached the target, and the company’s share price was jumping up and down over a period of weeks by more than the indicative trigger of 5 percent in a day,’ comments Broke. ‘If you looked at it over time, the share price was actually trending down, indicating that the bid wasn’t known about, but that wasn’t clear at the beginning. In this particular situation, the panel took a wait-and-see approach.’

In the case of De La Rue, the FTSE 100 rose 4 percent over the same period so the panel may have taken that as a mitigating factor. The company’s shares had also sunk over the summer following some bad news, so they had plenty of scope to bounce back.

Regardless of what happens to the share price, it’s worth pointing out that if a rumor is false, there is no obligation to say anything. ‘You don’t have to announce anything to stop a false rumor,’ says Broke. ‘You can just let that disappear into the ether. If people trade on rumors, that’s their problem. It’s only if the rumor is accurate that you have an issue.’

Shareholder obligations

There are other factors to consider when it comes to revealing approaches. A company’s regulatory obligation to make a statement aside, a firm may want to say something anyway to give its investors a chance to weigh the pros and cons of any prospective deal. This may be why Smith & Nephew made a statement in the end. ‘It could be that what actually forced it to get a statement out were calls from its shareholders asking, What’s going on?’ says Broke.

Shareholders don’t want every bid revealed, of course; that would cause unnecessary disruption to both the firm and its share price. Andrew Lynch, fund manager at Schroders, says he has 'no preference really' over when companies should be forced to make a statement. ‘I’m happy to leave it up to them and their advisers to judge,' he says.

Dealing with the Takeover Panel

The Takeover Panel is available at all hours of the day and night to speak to any company that is unclear about its disclosure rules. It will also call you if and when it has concerns. The main point of contact for the panel is usually a company’s corporate brokers or legal advisers, but it may on occasion speak directly with someone at the company – and that could be you.

Philip Broke, a partner at law firm White & Case, offers this advice to IR professionals: ‘When you’re dealing with the Takeover Panel, you are dealing with live bullets. There is no such thing as an off-the-record conversation. It’s not everyone who feels he or she has the experience for that.

‘And because the panel operates according to flexible rules, you really need to have experience of where it is coming from, what kinds of things worry it and what kinds of things don’t. Some IR professionals have the experience for this and some don’t. It’s not a criticism – it’s just what I’ve happened to come across.’