The valuations of social media companies are soaring, leading to comparisons with the bubble of 1999. But the evidence suggests otherwise

For those who lived through the first dotcom bubble, it’s hard to watch the soaring valuations of private companies like Facebook, LinkedIn and Groupon without a faint chill of foreboding. Is history about to repeat itself?

The story lines of these high-flying internet stocks certainly echo the Icarus-like rise of the 1999 pre-dotcom crash darlings. Just two years ago, LinkedIn was valued at $1.9 bn; today it has an implied value of $2.2 bn. Facebook was valued at $16 bn as recently as spring; the price Goldman paid for a 1 percent stake gave the company an implied value of $50 bn.

Even so, most experts believe we’re still a long way off the ‘mass hysteria’ that gripped the market during the first dotcom collapse. Certainly, there are some substantial differences between both the quality of the companies this time around and the kind of information available to potential investors. The valuations cited for Facebook and LinkedIn may be inflated but no one would confuse them with that poster child for dotcom ‘irrational exuberance’, Pets.com.

By the time the online pet goods supplier filed for an IPO in December 1999, it was locked in a price war with several competitors, had made just $5.8 mn in sales and had already lost $61.8 mn. But the hype machine was at full throttle. Pets.com had spent $20 mn on a marketing campaign that included a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and a $2 mn advertising slot during the Super Bowl.

The pitch for investors was: trust us, once we lock in market share, earnings will explode. Blinded by the hype, investors overlooked the lack of sales. And when the company went public, shares rose from $11 to $14. By the following November, Pets.com had reportedly burned through $179 mn and the company was dead.

‘Back in the day, most of those companies were cash flow-negative when they went public,’ says Steve Kaplan, a professor of entrepreneurship and finance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. The big difference today is that ‘all these new companies make money.’

Justin Byers, who is now a research analyst at VC Experts, worked on a trading floor during the first dotcom boom, and remembers everyone ‘trading on news and heresy. It was Vegas-style trading, fast and furious. When it all popped, we had grown men crying and lots of margin calls, and a month later it seemed like a lot of these companies weren’t even around anymore.’

The new normal

Today, even companies that are still private are already disclosing revenues, though their IR machine is likely to be more subdued, especially those of firms on the verge of going to market, due to pre-IPO restrictions on stock promotion. LinkedIn, which in January announced plans to go public, saw its net revenues nearly double to $161.4 mn in the first nine months of 2010, earning $1.85 mn in profit, according to its January SEC filings.

And although Facebook has not publicly released its numbers, Goldman Sachs allowed its clients a peak at the company’s revenues when it sought investors for a stake in the company earlier this year. In the first nine months of 2010, Facebook’s revenues were $1.2 bn with $355 mn in profit, on schedule to earn $1.6 bn for the year.

Some experts have speculated that even if those figures rose to $2 bn and $500 mn in profit, Facebook would still be trading at a price to earnings multiple of 100 – if you buy the $50 bn valuation – while Google trades at just 25 times earnings.

But Byers says the valuations being tossed around for Facebook are based on ‘a couple of thousand shares’ trading on private platforms frequented by wealthy qualified investors, and don’t necessarily reflect what the stock would be worth in a mass public offering with millions of shares trading hands daily.

‘Some people will pay whatever it takes just to say they own a piece of Facebook,’ Byers says of the small market for the private stock. ‘It’s a little bit of a stretch to get to a $50 bn valuation from such a small number of shares.’

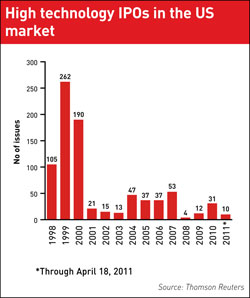

The very fact that shares of Facebook and other companies have not yet gone public differentiates today’s dotcom boom from the frenetic pace of IPOs seen in the 1990s. Alan Berkeley, a partner and securities regulatory lawyer at K&L Gates, says he is ‘certainly seeing considerable uptick in activity’, with regards to mergers, financing and commercial transactions for early and development stage companies. But the IPO market has not yet taken off, so any talk of a bubble is premature, he insists. ‘The fever is not what it was in 2000,’ Berkeley says.

Secondary issues

The rise of secondary trading platforms, which allow insiders to trade shares of companies that remain private, has added another twist to the market. Kaplan notes that by the time companies like LinkedIn and Facebook go public they will have substantially more shareholders than companies that went public in the dotcom era, which also usually means more information has been circulated. ‘There was no information in the dotcom day – things went public with no revenues, so you had no idea,’ he explains.

One private platform – New York and Palo Alto-based SecondMarket – allows the companies themselves to set their market parameters, deciding how many shares sellers can unload, who the qualified buyers are, and how often the market is open, says spokesperson Aishwarya Iyer.

The companies also decide how much financial information to provide, and are able to share company numbers through a secure data room, provided by SecondMarket. ‘It can be from exact details about funding that hasn’t been made public yet, or additional financial disclosure forms,’ Iyer says. ‘If the company chooses to share, it can.’

In a larger sense, the internet is far more mature, and that is enough to provide a realistic context in which to evaluate the business models of the companies seeking investment, says Gabor Garai, a partner at Foley & Lardner in Boston who heads the law firm’s private equity and venture capital practice.

He attributes the rising valuations of companies like Facebook to pent-up demand. Since the dotcom bubble burst, he notes, there has been a ‘huge shift in the marketplace with companies with a totally different set of technologies. Ten years ago, could you imagine people shopping while on their iPhone, and being in constant communication with Facebook?’

Caution is the byword

But because the market has been slammed by the subprime crisis and the recession, the opportunity to buy into these technologies has been limited. Meanwhile, cash has piled up on the sidelines, and investors are looking for big returns. Companies specializing in the new technologies, ‘just have not been offered to the capital markets over the last three or four years,’ Garai says.

The primary risk, he notes, is that, as happened in the dotcom boom, for every sector of the economy, there will be a flood of ‘me too players’ that will also go public, and ultimately that means there will be just too many players in every sector. ‘That hasn’t happened yet because we haven’t had that many IPOs,’ he says. ‘But it still may. We are at the very early stages of this new phenomenon.’

Nevertheless, some, like Illinois law professor Larry Ribstein, an expert in corporate and securities law, aren’t so certain. ‘Nobody knows there is a bubble while there is a bubble,’ he points out. ‘People are still arguing about whether the 1929 market was actually a bubble. Stock prices are based on expected earnings, which depend on a whole mass of judgment about the future.

‘In retrospect you could look and say Pets.com was a bubble, but around the same time everybody said we must have a bubble, because Amazon had a valuation larger than GM. As it turns out, that market was right: Amazon was the future and GM eventually went bankrupt.’