The EU has ended the obligation for quarterly financial reporting – although some exchanges still require it. How might companies use this new-found flexibility?

|

At a glance |

The change has prompted companies across the region to reconsider their reporting practices. Some have acted quickly, scrapping their first and third quarter (also known as interim) updates at the earliest opportunity. Most are weighing the situation and monitoring any changes made by competitors.

The options open to companies differ from market to market, however. In some countries, like France, it is now possible to stop interim reporting entirely. The same is true of the UK, which chose to implement the new rules a year early, in November 2014.

In other countries, local stock exchange rules complicate the picture. The German and Austrian bourses have both said companies must still provide quarterly reporting to be part of the prime market segment – although the minimum requirements for interim reports are greatly reduced under the new regime.

Continuing to publish full financial information four times a year is still an option. Many companies will continue to do this, for a variety of reasons ranging from industry dynamics to investor expectations.

Wherever they are based, European issuers now have important decisions to make about their reporting approach. This is ‘the issue’ at the moment in Germany, comments Kay Bommer, general manager of Dirk, the German IR association. (Follow this link to read a guest column from Bommer on reporting best practices for German companies.)

The change came about through amendments to the EU’s Transparency Directive. In 2013, the EU voted to abolish quarterly reporting for issuers on regulated markets and gave member states two years to implement this at the national level.

EU lawmakers hope the change will particularly benefit smaller companies, where the costs of quarterly reporting are felt most keenly, while also discouraging investors from focusing on short-term performance. When setting the new rules, the European Commission said ‘obligations to publish interim management statements or quarterly financial reports represent an important burden for many small and medium-sized issuers... without being necessary for investor protection.’

The commission makes certain allowances, however, and one of those states that regulated markets are entitled to require ‘additional periodic financial information in all or some of the segments of that market.’

Prime requirements

The German and Austrian stock markets have taken up this option for their prime segments, although in different ways. The former says interim updates need as a minimum only a brief description of the financial situation and key events. By contrast, the latter requires companies to report key financial data while commentary is less important.

In both these markets companies have strong incentives to continue with first and third quarter reports. Prime Standard-listed companies will not want to give up their status. Non-prime companies, meanwhile, may want to demonstrate their fitness for future inclusion. The decision for most will revolve around how to change the size and content of their quarterly output.

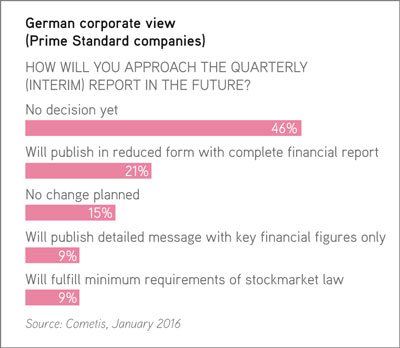

A study by IR firm Cometis of German prime market companies finds that only 15 percent plan to make no changes, although a large proportion remain unsure of what to do (see German corporate view, below).

Bommer – bringing together all the surveys he has read and anecdotes he has heard – predicts that, for the first quarter of 2016, 40 percent of this group will do some kind of quarterly financial report and 30 percent will do an interim update focused on commentary. The remaining 30 percent are undecided, with a large percentage likely to defer their decision until Q3.

Reasons to continue

Why might companies continue to publish quarterly financial information? There is no single reason: some need quarterly audited financial information to support fixed income programs. For others, it may suit the flow of the business or industry. Those with US shareholders may want to retain quarterly reporting to provide what their US holders are used to.

One hope is that cutting back the size of reports will help to make them more effective communication vehicles. At some companies, first and third quarter updates have grown to more than 100 pages. Bommer is encouraging German companies to use this moment as an opportunity to try out new reporting formats. One idea is to create presentations and then file those as the interim updates. Nobody says a quarterly report needs to be ‘A4 and only printed on paper,’ he says.

In other markets, where the big exchanges do not have their own quarterly reporting rules, a far bigger question is being wrestled with: should interim statements stop completely? Certainly, pitfalls await those that take the plunge. Companies must beware creating a vacuum of news and contact with the market – the kind of space investors and analysts like to fill with speculation.

Furthermore, sections of the investment community will worry if they lose two of their four regular reports, especially smaller firms that don’t get the same access as larger ones. Resistance may also come from the sell side: a survey of CFA UK members in July last year finds 43 percent prefer quarterly reporting, while the same proportion think semi-annual updates are best.

The UK had a head start on other markets by bringing in the rule change a year. Since then, companies like National Grid and Diageo have stopped producing interim management statements (IMS). In France, meanwhile, it’s reported that two smaller companies, AFONE and Laurent-Pierre, have also dropped interim updates.

Yet, despite this freedom, there is a reluctance to pull the plug among most issuers. A survey by the UK’s IR Society last August finds that, while two fifths of firms are considering a change of approach, just 2 percent plan to stop producing the IMS over the next 12 months (see UK corporate view, below).

Those considering an end to interim reports should examine their industry dynamics and business operations to see what kind of reporting fits the bill. They should also sound out the investment community on its views.

‘To report on a quarterly basis or not depends on whether the performance and outlook for your business can change from quarter to quarter,’ Aarti Singhal, director of IR at National Grid, told IR Magazine earlier this year. She explained that the IMS had become a ‘box-ticking exercise for National Grid where the financial performance doesn’t change much from quarter to quarter.

‘It is best to take the lead from investors on what level of disclosure and updates are helpful to them in tracking the performance of the company,’ added Singhal.

IROs who have moved away from interim updates point out they have other methods of keeping up communications with the market. For example, National Grid has an IR newsletter that ‘can be sent out whenever is appropriate,’ said Singhal.

Similarly Diageo has a ‘full program of updates’ that includes regular calls with the company’s presidents, according to head of IR Catherine James. ‘I wouldn’t suggest that any company move away from quarterly reporting if IR does not have a number of alternative routes for communicating with investors,’ she said, also speaking to IR Magazine earlier this year.

If the experience of the UK is anything to go by, dropping quarterly reports entirely will not be a popular option for the rest of Europe – at least for now. Certainly, prime-segment companies in Germany and Austria have little choice but to maintain four updates a year. The new rules, however, have ushered in a new era of flexibility. We can expect widespread changes to reporting habits across the region.

|

Corporate reporting checklist |

This article appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of IR Magazine