It’s questionable whether the latest increasing trend to provide guidance is in a company’s interests

Marmite, Persil and Vaseline are everyday items – products you would think provide pretty steady financial performance. We all eat, wash and find a multitude of uses for applying petroleum jelly, whether we are in the depths of a great recession or the middle of a huge speculative bubble. Yet last year Unilever, the owner of those brands, gave up on providing financial guidance to the City. Chief executive Paul Polman said companies that set targets, only to revise them, were not credible.

That initially sounded like a controversial view, but it became less so. GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceuticals giant, is another massive ‘defensive’ company that stopped providing the market with guidance, while ending its long-running practice of providing short-term earnings forecasts. Its chief executive, Andrew Witty, says he wants the market to focus on long-term goals rather than the next quarter or two of trading.

Anthony Nutt, head of UK equities at fund manager Jupiter, thinks these two massive companies have got this correct. ‘Glaxo and Unilever are right in withdrawing explicit short-term guidance,’ he says. ‘Both invest significant sums in products and innovations that have long lead times to market. Effective communication of longer-term strategy and financial goals are a better way of assessing management effectiveness.

‘Quarterly guidance is unnecessary and potentially dangerous as it can start dictating the way a business is run. It is possible that companies run with a medium/long-term perspective may prove more likely to create shareholder value. Increasingly, global competition should ensure well-run businesses remain efficient.’

Certainly this has been an argument that chimes more and more with companies’ actions during the financial crisis, when many pretty much abandoned guidance – albeit probably for reasons of poor visibility rather than deep conviction. But is the practice of the ‘nod and the wink’ picking up again?

The investment community view

IR magazine’s Investor Perception Study, Europe 2010 asked a sample of buy-siders and sell-siders the following question: with the worst of the market crisis behind us, are companies now being more transparent and providing more guidance and access to management? One sell-side respondent in Switzerland replied: ‘The worst over? Are you joking? We’re not even halfway through and no, transparency is not improving but then neither is the view of the market. It’s only possible to be transparent when you’re clear and there are precious few companies around that are.’

There were 200 responses to the question in total, with 54 percent saying there was no more information or access than before. But around 30 percent of respondents said communications had improved in the past year, while the remaining 15 percent said it was a mixed picture or variable from company to company and sector to sector.

Typically, there are three types of guidance. First, there are formal targets in press releases, such as company X targeting EBIT of Y million this year. Second, there are strategic goals, such as this company aims to grow volumes in issuance by 6 percent to 14 percent per year on a like-for-like basis. Third, there is informal guidance or steering of forecasts from someone at the company, which is usually done by an IRO, but sometimes by the CFO or someone else.

One sell-side analyst based in London said: ‘I think those companies that have generally done the first – such as Accor, Carnival, Edenred, Paddy Power, Royal Caribbean and Sodexo – have continued to do so throughout the downturn, although there have been some that have widened their targets to reflect the volatility. Those companies that stick to strategic goals (Compass, Edenred) have tended to continue to do the same. Companies with loose guidance from IR or management have been variable throughout, and they always will be. We would always question a company’s motive when trying to steer consensus in a certain direction or to a certain number, without going the full distance and having a formal target.’

The corporate view

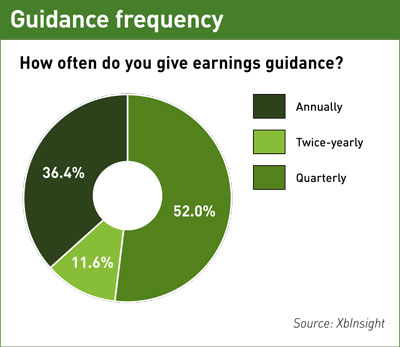

More companies seem to be giving guidance than not, however. In June 2010, the global survey of IR practice carried out by XbInsight, IR magazine’s research arm, found 58 percent of companies saying they were still giving guidance. But the figures swing wildly from market to market, with the US as high as 70 percent, the UK at 32 percent, and Asia-Pacific coming in right in the middle at 51 percent. Of those that do give guidance, 68 percent of US companies do so quarterly and 83 percent of UK respondents do so twice a year. In Asia-Pacific 53 percent guide quarterly and 29 percent do so annually.

The trend for American IROs to issue more guidance is backed up by Pierre Lapointe, a global macro strategist at Montreal-based broker Brockhouse Cooper. ‘The number of pre-announcements has increased over the past few quarters as earnings visibility has improved,’ he says. ‘Over the past three months, US companies have issued 1,237 preannouncements. But the number of guidances is still low historically, which also means the number of profit warnings is now close to a 10-year low.

‘We further note that the ratio of negative to positive preannouncements is now at its lowest level on record. This bodes well for upcoming earnings releases as managers are less downbeat than usual. In the US, the consensus of analysts expects S&P 500 earnings to increase 14.7 percent over the next 12 months. If managers had any doubts that they would not be able to meet this lofty earnings growth estimate, they would have warned the market’.

Still, as we have seen all too recently, there remain surprises kicking around. But analysts don’t necessarily see a company under-performing market expectations as an indication of bad IR, any more than they see outperforming market consensus as good IR. Betfair, the online betting exchange recently floated in London, saw its shares slump by 16 percent after lackluster figures spooked investors who had bought into the company’s bullish growth story. A failure of IR? It doesn’t really seem so. ‘I have no complaints about the investor relations,’ says one analyst, who is bearish on the shares. ‘The company has always been very open and helpful.’

Conversely, surprising the market on the upside does not represent a coup for the IR manager. ‘Gaming market expectations by IR managers is a widespread practice,’ says Nutt. ‘Talking forecasts down a few percent ahead of results only to beat revised expectations by a few percent is a pointless exercise, and increasingly raises fears that these kinds of companies are running to meet short-term financial goals and will underperform over the long term.’

If analysts were asked to give guidance to IROs about their consensus view on this topic, here’s what one sell-side analyst would say to them: ‘Good IR and corporate communication are invaluable, and we would always rather have that than have limited communication from the company and have to use our own resources. Having said that, however, it is clearly important to have differentiated views to discuss, and we formulate those through other channels, as the company is duty-bound to give the same information to everyone in the market.’

In practice, views probably depend on what an analyst has predicted beforehand, particularly if he or she has been made to look clever or foolish. And certainly there are analysts who claim to revel in poor IR, chiefly because it provides an opportunity to steal a march on peers. That’s not in the interest of any IROs, who should stick to the old goal of avoiding surprising the market at all costs; whether that is best done through guidance or not may depend more on the profile of the individual company than on anything else.