The Asian IPO market has slowed to a standstill this year, with many companies unable to list because of low valuations. US and UK investor interest remains strong, however, particularly in Chinese stocks

Eighteen months ago, as financial markets across the globe reached their peak, investment banks, stock exchanges and law firms were crawling all over Asia looking for the next company to float. Now bankers in Singapore, Hong Kong and London say the Asian IPO market is, in effect, closed for business.

More than a dozen Indian companies have pulled their IPO this year, the Indonesian government has put off all listings by state-owned companies until 2009 at the earliest, and in Saudi Arabia as many as 80 floats have been put on ice.

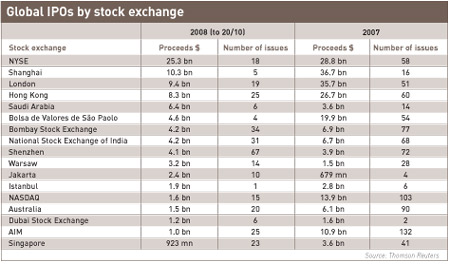

It’s a similar picture elsewhere (see Global IPOs by stock exchange, below) but the collapse of the IPO market has been particularly pronounced in Asia, where the major international stock exchanges were competing so fiercely to win new listings. Now, as the year draws to a close, potential new issuers, corporate financiers and exchanges are trying to work out the best way forward for 2009.

The outlook is not great, with many regional economists warning that the knock-on effects of the slowdown in the US and Europe have yet to truly hit Asia. But market participants are using the lull to build up future business, with a strong focus on China.

‘A 50 percent drop in the number of new issues is not so bad given the current situation,’ says Jane Zhu, head of the London Stock Exchange’s (LSE) Asia-Pacific business in Hong Kong. ‘Other exchanges are doing far worse. We’re taking a long-term view in Asia; it’s easier to see people, hold meetings and build foundations when the deal flow is less busy.’

Zhu insists that while deals have slowed down, ‘the inquiries never stop and the pipeline is buoyant.’ The LSE’s Beijing office, opened by UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown earlier this year, is still holding one or two marketing events a month, and the LSE has recently launched a dedicated guidebook for Chinese firms considering a London listing. ‘It’s not just China,’ Zhu adds. ‘We’ve also had interest from Japan, Malaysia, Mongolia and Taiwan.’

Mike Edwards, who heads up the Singapore office of law firm Cains, has helped bring a number of Indian companies to London’s Alternative Investment Market (AIM). He agrees that the market downturn has a silver lining. ‘Investment bankers and companies are less busy now than 12 months ago, so they’ve got much more time to meet and come up with creative ideas,’ he explains.

Ultimately, however, Edwards accepts that the wider picture is bleak. ‘The tap has definitely been turned off,’ he says. ‘The problem is largely one of value. There are some very good companies interested in listing, but the low value investors place on them means it’s not worth their while to sell.’

The waiting game

Companies float on the stock market either because the owners want to cash in their stake or because the company needs capital to fund its existing operations or expand. Even those in the latter category are putting off their IPOs for now, Edwards adds. ‘Firms might well need the capital but if a potential investor is offering you only two times profits, it’s better to mothball projects,’ he points out.

The global nature of the current crisis has put paid to the idea that Asia’s emerging economies could simply ‘de-couple’ from events in the West, but politicians and economists in Asia still maintain the region is in a much better position to weather the storm than it was during the 1997 financial crisis. This gives firms and their advisers hope that Asian economies may see a softer landing and a swifter recovery.

‘The IPO market is probably not as bad as 1997-1999 in terms of mindset,’ notes Quek Peck Lim, chairman of Asian IR consultancy Oaktree Advisers and Singapore-based corporate finance house Prime Partners. ‘We’re maybe more relaxed than those in the West because we’ve seen it all before in 1997.’

New issues are still coming out, Lim says, but only very small amounts of money are being raised. ‘The hope is that more money at better valuations can be raised later,’ he continues. ‘But the issuer’s message has to be sharper; companies need to be able to convince the market of their story.’

‘Companies should remain focused on the fundamentals,’ adds Eric Landheer, NASDAQ’s head of Asia-Pacific. ‘It’s a waiting game, with a lot of uncertainty in markets around the world.’

All eyes on China

Over recent years, stock exchanges in London, New York, Singapore and Hong Kong have been positioning themselves to capitalize on the eventual flood of overseas listings that will come out of mainland China. Despite the global crisis, many in the international financial community are still looking to China to provide the next great source of IPOs.

While annual growth in China has slipped below 10 percent for the first time in more than five years, ‘the Chinese growth story remains intact,’ according to Landheer. ‘There is a continued interest in listing in the US, and US investors will retain an appetite for Chinese stocks,’ he explains from his Hong Kong office. ‘China is our largest single foreign market and we expect it to play an important role in the future.’

Landheer adds that NASDAQ’s Asian pipeline is ‘very strong’, with the majority of companies interested in a US listing operating in the media or clean technology sectors.

The LSE is also working hard to attract Chinese companies. CEO Clara Furse and chairman Chris Gibson-Smith both visited Beijing earlier in the year, and Martin Graham, director of markets and head of AIM, was touting for business in China in October.

‘There are a number of Chinese companies on AIM that are thinking of moving up because they are big enough now,’ Zhu points out. ‘We are also trying to find private companies that are large enough and good enough to join the main market directly.’

With much closer geographical and political links to the mainland, it’s hardly surprise that the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) has also been out on the marketing trail, visiting more than 30 Chinese cities in the first half of the year. ‘We are seeking to position HKEx as China’s international exchange, complementing the mainland domestic exchanges and partnering the mainland in its overall economic development,’ says a spokesperson for the exchange.

Although the Hong Kong and Singapore exchanges and their smaller regional peers are trying to compete with the likes of NASDAQ and the LSE, Landheer believes that, once equity markets start to recover, Asian companies will continue to be attracted to the US and Europe because of the presence of sophisticated institutional investors with deep pockets.

Edwards echoes this sentiment. ‘While listing Asian companies in Asia must make some sense, London still has some major advantages in terms of the maturity of the market, the depth of the pool of capital and the fact that every major financial institution is there,’ he observes.

Just as emerging markets tend to outperform developed markets in the good times, so the more well-established markets typically prove more resilient in a downturn. ‘There are those companies that said, We’ve got such a great price/earnings multiple in our local market, why would we go to the US and deal with SOX and all the other regulatory costs?’ notes Landheer. ‘But now these developing markets are down even further. While NASDAQ doesn’t compete with these local markets, ultimately the deepest pools of liquidity remain in the US and Europe.’