South Korean pharmaceuticals firm Dong-A is part of a gradual movement away from an entrenched culture of family ownership to enter a global marketplace

South Korea is a country that owes a significant amount of its rapid development to the chaebol that dominate its corporate landscape.

A form of family-controlled ownership, chaebol are conglomerates or ‘business groups’ that allow the controlling family to govern through a series of complex cross-shareholdings.

The South Korean government used chaebol to kick-start the economy after the Korean War ended in 1953, and the oligarchic system has served the nation well, allowing it to industrialize rapidly.

The government has now taken some steps to free up the market, but its hands remain largely tied when it comes to the controversial subject of chaebol.

Despite the prevalence of related-party transactions, many still invest in South Korea because of its growth story. Problems arise for companies when growth plateaus, however. The country has suffered badly in the current economic downturn, with exports now reportedly growing at their slowest pace for the past year and a half.

The more forward-thinking South Korean firms are realizing that in the long-term, they will need to attract greater foreign investment, forcing them to reassess their internal organization.

Attracting attention

One such company is pharmaceuticals firm Dong-A. It has followed the lead of firms such as POSCO Steel, which overhauled its corporate governance structure when it was privatized, before it went public again.

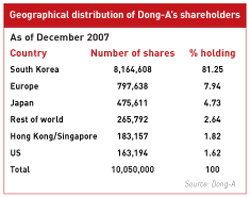

Dong-A listed in 1970 and is South Korea’s largest pharmaceuticals company. It has been producing the country’s best-selling taurine energy drink for nearly 45 years, something that has helped it attract a sizeable number of non-domestic investors: it currently has a holding of 20 percent by foreign shareholders.

Dong-A’s investment story hinges on the fact that South Korea is the most rapidly aging country among the 30 OECD nations. Demand for drugs is high and, as a result, the South Korean pharmaceutical industry has been growing at an annual rate of more than 10 percent for the past few years.

Despite its attractive growth story, however, Dong-A’s chairman Shin-Ho Kang felt reform was needed. His resolve was strengthened after management faced a challenge from within its controlling family.

‘We are a mid-sized company that is little known outside Korea, so we have been putting in a lot of effort to improve communications with our foreign shareholders,’ explains Mani Han, general counsel of Dong-A’s legal team. The firm recently published its first English annual report, and launched an English-language website in August 2008.

Strengthening relations

Dong-A kicked off its governance overhaul with a corporate governance workshop for its senior management. ‘Although corporate governance is well known in South Korea, it’s still a relatively new concept,’ explains Han. ‘Transparency is always an issue, but we want to improve corporate governance in order to further boost our relations with the shareholders.’

The company worked with an external consultancy to educate management on the benefits of good corporate governance on shareholder value. Justin Reynolds, a partner at US and European business adviser Sodali, estimates he and his colleagues put in around nine months of continuous work with the firm.

As part of its reforms, Dong-A took the step of amending its articles of incorporation to improve corporate governance and allow the company to implement an investment advisory committee and outside director nomination committee within the board. The company added an outside director to the board soon afterwards. It now hopes to add one outside director a year with the ultimate aim of having a majority of outside directors serving on the board.

Long road ahead

Having reviewed its internal governance controls, Dong-A’s IR team went on the road in an attempt to woo long-term institutional investors in New York, Boston, London, Paris and Amsterdam.

The transition from family control to an independently run company is not an easy one, however. The chaebol-style cross-shareholdings at Dong-A are unwinding, but it’s a very slow process. As South Koreans increasingly live and study abroad before returning to their country, however, questions are increasingly being asked about the nature of the current system.

A further catalyst for the development of corporate governance in South Korea was the presence of governance experts from all around the world at the recent International Corporate  Governance Network annual conference, which was held in Seoul earlier this year.

Governance Network annual conference, which was held in Seoul earlier this year.

But with the government now relatively silent on the future of the country’s chaebol, the impetus for change must come from the companies themselves – and this may pick up pace as the market suffers in the face of the current economic turmoil.

As valuations continue to falter, more and more companies will be marketing themselves as reliable long-term investments. Expect to see more businesses following Dong-A’s lead.