IROs increasingly need an understaning of Islamic finance, especially those targeting the Middle East

More than 20 percent of the world’s population is Muslim, but Islamic finance is still shrouded in a veil of mystery. While it is commonly known that Shariah law forbids usury – the lending of money for interest – Muslims and non-Muslims alike are becoming anxious about the complexity and variety of Shariah regulations.

Islamic finance has withstood the economic crisis in good shape and Islamic banking plays a growing role in capital raising worldwide, not just in Muslim countries. Their IROs may not even realize it, but western corporate giants like Microsoft, BP and GlaxoSmithKline are already Shariah-compliant. Your company may be, too.

To comply with Shariah law, a company must be halal, so sin sectors like alcohol, tobacco, arms, pornography and gambling are strictly forbidden. In addition, Islam considers conventional financials – banks, insurers and credit card companies, for example – unlawful as they are heavily involved in usury, or riba. There are also certain ceilings for interest-earning activities. That leaves a large universe of companies eligible for the growing pool of Shariah investment.

Is your company Shariah-compliant? That’s a question all IROs should be able to answer, especially if the Middle East is on their company’s targeting radar. What’s more, IROs in countries like Malaysia need to be able to explain the structure of sukuk, or Shariah-compliant debt-like instruments, to non-Islamic investors in the West. Islamic investors will naturally be concerned about the eligibility of those instruments, whether or not they’re issued by a company from a Muslim country.

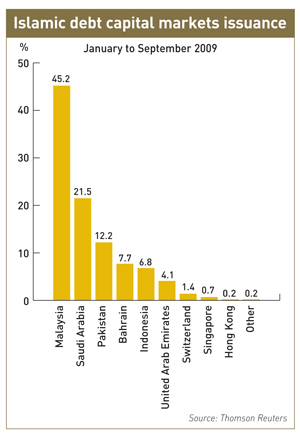

Malaysia leads the way The issuance of sukuk, sometimes called Islamic bonds, has been on the rise across Asia and the Middle East for the last decade. Total outstanding sukuk rose from $8 bn in 2003 to around $100 bn in 2008, according to Saudi Arabia-based Jadwa Investment. Thomson Reuters shows new issuance peaking at $28.1 bn in 2007.

The issuance of sukuk, sometimes called Islamic bonds, has been on the rise across Asia and the Middle East for the last decade. Total outstanding sukuk rose from $8 bn in 2003 to around $100 bn in 2008, according to Saudi Arabia-based Jadwa Investment. Thomson Reuters shows new issuance peaking at $28.1 bn in 2007.

Growth was temporarily halted by the financial crisis in 2008, but 2007’s pace was recaptured in mid-2009. Malaysian markets hosted the largest proportion (45 percent) of issuance in the first nine months of 2009, followed by Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, while Switzerland has the highest rate of issuance for a country without a Muslim majority (see Islamic debt capital markets issuance, right).

‘It’s an interesting time for Islamic finance, especially in this post-crisis period,’ says Rushdi Siddiqui, global head of Islamic finance at Thomson Reuters. ‘There is interest in knowing why there have not been bailouts and bankruptcies in Islamic finance, which presents an opportunity for this niche market to put forth the case for asset-backed financing.’

These developments have not been nurtured in isolation. Siddiqui adds that ‘if Singapore, Hong Kong, the UK and now Paris want to be seen as comprehensive financial hubs, new ideas and efficiencies are very important.’

That said, the market is still blighted by regional variations and academic dispute, notes Ben Franz-Marwick, head of IR at Emirates NBD, the biggest banking group in the Middle East by assets managed. In February 2008 the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) ruled that some of the larger sukuk structures were not Shariah-compliant. Six core principles for the structuring of sukuk transactions were established, but wider consensus has not overcome regional differences. For example, Malaysian Shariah authorities allow sukuk to be traded but the AAOIFI does not.

There are also different criteria used for the swiftly evolving array of Shariah equity indexes such as the FTSE Shariah Global Equity Index Series or the Dow Jones Islamic Market Indexes. Siddiqui feels ‘the objective of achieving standards will happen slowly’ with the passage of time.

Not exactly debt

Sukuk are Islamic financial certificates that share the qualities of bonds. They’re best described not as debt but as trust in certain Shariah-compliant assets, and their most common form is Sukuk al-Ijarah. Investors, in effect, lease back the assets over a specified period for a specified cost; this ‘rent’ replicates conventional interest on a fixed-income debt security. Sukuk therefore behave like standard non-Islamic bonds.

This difference in structure makes education a direct concern of IROs preparing for an Islamic finance initiative, whether the issuance is targeted at Islamic or non-Islamic investors. ‘Investors are only recently getting acquainted with the principles of Islamic finance,’ says Bernardo Vizcaíno, managing director of Islamic finance consultancy Amsar Partners.

When marketing sukuk to non-Islamic investors, IROs need to be able to translate the sukuk structure. Franz-Marwick says that even if this is simply in order to verify the risks or possible returns from the cash flow structure behind the sukuk, IROs must be well prepared and educated before the roadshow.

Most Muslim institutions employ their own Shariah scholars to check the validity of sukuk, as do index setters. Andrea Weidemann, a spokesperson at Dow Jones Indexes, emphasizes that the Dow Jones Islamic Market Indexes use an independent board of five scholars from diverse regions.

The growth of Shariah indexes doesn’t mean there is much uniformity, however. Franz-Marwick says IR should focus on making sure ‘the issue is watertight and valid in as many regions as required.’

Siddiqui believes there is interest in achieving global consensus. ‘Bodies like the AAOIFI and the Malaysia-based Islamic Financial Services Board have done a good job on standards and prudential regulations, respectively, but these are early days,’ he says.

Vizcaíno is more pessimistic. ‘This scholarly back and forth may bring about more confusion than clarity,’ he warns. ‘There is no industry body properly representing investors and consumers.’

Being engaged and market-aware is the norm in IR. New financial structures, their regional novelties and moral dimensions are a challenge, not a chore, and great rewards are possible.

Glossary

- Al-Ijarah means leasing. Sukuk al-Ijarah are the most common forms of sukuk (see below).

- Halal is any item or action allowed by Shariah law.

- Haraam means forbidden.

- Riba is usury, which is forbidden by Shariah law. It is similar to the pre-Islamic Arab word for ‘increase’.

- Shariah law is the Islamic body of law that regulates civil, criminal and moral action for Muslims.

- Sukuk (or sakk – singular) are asset-backed financial certificates that are Shariah-compliant. They’re the Shariah equivalent of fixed-income bonds.