Research shows analysts whose forecasts are off consensus in the wrong direction are more likely to dig their heels in

People are supposed to learn from their mistakes. But often that's not true, particularly in the world of sell-side analysts, according to some new research. The study suggests that when analysts make blatantly bad calls, they get their backs up and become entrenched in their opinions.

John Beshears, assistant professor of finance at Stanford Graduate School of Business and Katherine Milkman, assistant professor of operations and information management at the Wharton School, argue that analysts who are outside the consensus of other analysts feel pressure ‘to invest more time and energy than usual’ to support their positions. Furthermore, they become ‘particularly reluctant’ to back down, even in the face of information that says they are wrong.

‘They go out on a limb and say something that isn't popular,’ Milkman says in an interview with IR Magazine. ‘New information says they were way out of line. Instead of moving back to consensus, they dig their heels in even further than the ones who were closer to consensus.’

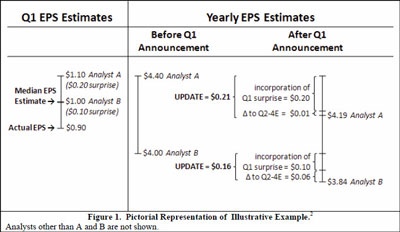

Using Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System (I/B/E/S) data from January 1990 to March 2008, they looked for companies that announced results that sharply differed from consensus forecasts. Analysts whose opinions were significantly off from the consensus, but in the wrong direction, would update their forecast for subsequent quarters even further in the wrong direction.

For example, say that analyst consensus for earnings of company X were $1 for the first quarter and $4 for the year. However, the company came in at $0.90 for the quarter. An analyst who had forecast $1.10 for the quarter might reduce his or her yearly forecast, but probably by a smaller amount than an analyst who had predicted $1.

Such behavior might make sense if there were a benefit to the analyst. ‘It could be rewarding to be stubborn, in terms of accuracy or clients listening to you,’ Milkman says. ‘Or it could be stupid. We don't see any redeeming value for it when we go hunting in a number of different ways.’

According to the authors, it's not the first study to show that sell-side analysts can resist fact: ‘Previous research has demonstrated that sell-side stock analysts display overconfidence (Friesen and Weller 2006; Hilary and Menzly 2006; see also Deaves, Lüders, and Schröder 2010) as well as a tendency to make upwardly biased forecasts (DeBondt and Thaler 1990), to exhibit cognitive dissonance (Friesen and Weller 2006), and to overreact to positive information but under-react to negative information (Easterwood and Nutt 1999),’ notes the research.

As amusing as this would sound from a disinterested view, such behavior affects IROs and their companies. Analysts who consistently set expectations too high or low can create ill will toward the business they cover. Trying to present factual information to the analyst may not work, because they're already discounting the facts of actual results.

‘It's a fundamental problem with things we find in this literature,’ Milkman says. ‘How do you talk them out of thinking about the world in an erroneous way?’ One possibility, she thinks, is to go around the analyst to the markets, addressing estimates that are consistently and significantly off from consensus. ‘You could point out to the markets that this one person is pulling down the consensus, so it's not something you should put weight on,’ she says.