While many companies grapple with the effects of the economic crisis, others are scoring points for transparency about their exposure. As events unfold, good communication will be more vital than ever

It’s hard not to suspect that some of the larger banks, mortgage lenders and insurance companies claimed by the current economic crisis might have fared better if they’d heeded the fundamentals of good IR and communicated more openly.

By contrast, some financial services companies are scoring points for transparency in this unparalleled economic debacle by candidly discussing their market positions and issuing press releases that detail exposure to troubled institutions.

Hulus Alpay, who heads the IR practice at Manhattan-based Makovsky + Company, cites the example of Citigroup issuing a series of press releases on the firm’s ties to Lehman in a way that makes it look transparent and communicative. Such actions are definite pluses with panicky investors, and Alpay praises Citigroup for having ‘bucked the trend and commented on a situation that companies traditionally would not have commented upon.’

Several other companies also led by example: Torchmark disclosed its investments in AIG, Lehman Brothers, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Washington Mutual (roughly 2 percent of total invested assets); Aetna filed a statement with the SEC, noting its $234 mn exposure to AIG and Lehman. In Canada, Sun Life Financial, Manulife Financial and Kingsway Financial Services all issued press releases detailing their exposure to specific troubled US financial institutions.

Other large institutions sought to distance themselves from a bad situation by issuing press releases about the bullets they had dodged: AXA Group and Jarden both put out releases describing their exposure to Lehman Brothers and AIG as ‘not material’.

As the practice of IR has matured, many companies are gaining high marks for sticking close to the IR rule book. When the market crashed in 1987, Bernard Compagnon, managing director of investor relations at Gavin Anderson, recalls that ‘companies basically cancelled everything, closed for a while and then timidly showed their noses again a few months later.’ This time, he says, IROs don’t need to be educated in the basics of crisis management.

‘Continue as you have planned,’ recommends Compagnon, who works primarily with public firms in Europe. ‘Don’t diminish your level of activity at all. This time around, I don’t find this message a hard sell.’

Silence is dangerous

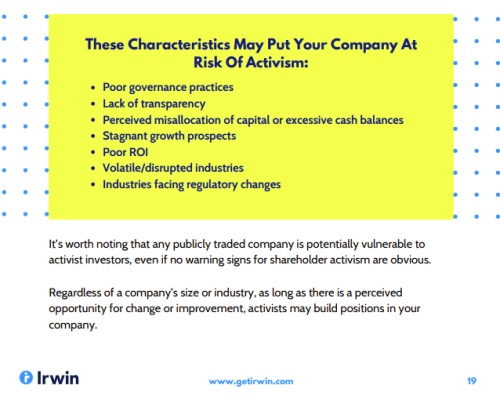

In skittish markets, keeping silent will be construed negatively, experts agree. ‘Right now, investors are going to sell first and ask questions later,’ says Alpay. ‘Companies that stay quiet will be gobbled up by their competitors, lose investor confidence and be prone to shareholder activism and class-action lawsuits.’

While almost everyone is convinced that communicating is the right strategy, IROs are debating precisely what information to convey. Jeff Morgan, president and CEO of NIRI, offers this advice: ‘This is the time to explain how debt affects your company. And it’s the time to explain how the loss of Lehman or AIG – or even how LIBOR – affects you.’

Roger Pondel, president of Los Angeles-based PondelWilkinson, offers similar advice. ‘In delivering the company’s story, place greater emphasis on strong balance sheets,’ he suggests. ‘Discuss cash positions, and reiterate capital requirements. Get conservative is the mantra for what is likely to be a rough 2009.’

Yet not all IROs are being inundated with calls from institutions and sell-side analysts. ‘I would have expected to need to hold hands and talk a lot more with the guys covering the story,’ says Lorne Gorber, vice president of global communications and IR at Montreal-based CGI. He suspects that many institutional investors are so preoccupied with their tanking financial services holdings that they’re not losing sleep over stocks that have fallen less sharply than the broader market.

Research analysts may also be too preoccupied with their own personal situations to pursue IROs aggressively. As Gorber notes: ‘It’s hard to focus when you’re wondering whether you’ll have a job next week.’

Morgan has a similar observation. ‘The analyst community is in upheaval, especially those tied to an investment banking or broker-dealer firm,’ he says. With Lehman and Merrill Lynch gone, there will almost certainly be fewer analysts left to render verdicts on public companies, making one’s relationship with each individual analyst that much more critical, he adds.

Given the current economic climate, analyst and credit downgrades are inevitable. ‘We’re on an early wave of many credit downgrades. Just look at the headlines to see why,’ says Glen Grabelsky, director of the credit policy group at Fitch Ratings.

With an onslaught of downgrades approaching, IROs need to communicate more, not less. ‘During this period when hold or sell decisions are being made in a state of emotion, those firms where management stays visible and communicative will have a far greater advantage in retaining their investors,’ observes Pondel.

Meanwhile, Alpay urges IROs to understand the rationale behind rating changes in order to communicate clearly with jittery investors. ‘In good times and bad,’ he says, ‘you must understand the thesis of the downgrade so you can come back with the counterpoints that can get analysts back on track, or at least recognize when things turn around.’

Smart targeting

Although communication is critical, certain conversations are more urgent than others. ‘If mutual funds are facing big redemptions, there’s not a lot you can do,’ says John Palizza, who teaches a graduate IR course at Rice University. A better strategy, he suggests, is meeting with smaller money managers actively seeking market opportunities.

Taking calls from hedge funds is also important, advises Alpay. ‘You’ve got to understand their thinking and feel their pain to know how they will react,’ he says. ‘It’s that knowledge that lets you maintain control of the situation, advise your management team and ride out this storm.’

MTS Allstream, a Winnipeg-based telecom company with $2 bn in sales, is using the economic downturn as an opportunity to ‘meet new investors and travel to new cities,’ says Ian Chadsey, MTS’ vice president of IR. ‘In times like these, investors look to stocks that pay big dividends. We have to make sure people know we pay the third-highest dividend on the TSX.’ Chadsey visited San Francisco and Boston for the first time in early October as the world’s stock markets unraveled. ‘There are big markets out there like Denver, Houston, Milwaukee and Boca Raton,’ he notes. ‘If you’ve never been, it’s time to get out there.’

Growth companies that have been pummeled may also want to press their case with an altogether different audience. ‘If your stock has gone from $100 to a single digit, you have a great opportunity to talk to value investors and bring up the valuation drivers that could get them interested,’ says Alpay.

Show restraint

Almost everyone agrees that challenging times are when it’s most important to stay the IR course. There are caveats, however. Telling your story is essential, says Palizza, but being a Pollyanna can prove a turn-off. ‘If you are too loud about opportunities at the expense of others, you can alienate people,’ he says.

He also warns IROs against indulging in happy talk. ‘You want to ground everything you say in fact and rational supposition,’ he adds.

Gorber questions the wisdom of rushing out press releases full of positive developments, and is considering how best to time CGI’s announcements. ‘Do I want to throw good news into the fray and perhaps have no one notice because things are going so poorly in the markets?’ he asks.

Finally, Alpay is convinced a blanket refusal to comment on rumors could prove disastrous in the current environment. It would be absurd, he says, to refrain from refuting rumors that have the potential to bring about your company’s demise. ‘You may need to comment on some rumors,’ he concludes. ‘Think of it this way: if you don’t comment now, you may not have the opportunity to set the record straight later – because you might not be around.’