Volatility and short-termism are giving IROs the jitters. But the former is mostly just noise and the latter isn’t as bad as it’s perceived

On any given day during earnings season, companies meet, beat or miss earnings estimates, and their stocks move up and down according to the laws of supply and demand, sellers and buyers. It’s that simple. Or is it?

Most of us still think of the stock market as though traders were gathering under a buttonwood tree on Wall Street like they did more than two centuries ago.

They buy low and sell high, hopefully waiting a while in between. Information seeps in and out and, sooner or later, shows up in stock prices.

But the buttonwood gang never dreamed of dark pools or high-frequency trading (HFT) or computer algorithms that trade billions of dollars without regard for company fundamentals; a $600 tn global derivatives market didn’t figure in their nightmares.

They couldn’t conceive of world markets so entwined that a Slovakian vote on a Greek bailout could dominate a New York hedge fund manager’s day.

Down the rabbit hole

‘We’ve gone down the rabbit hole. We’re trying to act as though things have not changed, when all around us everything is completely and utterly transformed and distorted,’ declares Tim Quast, founder of ModernIR in Denver, Colorado.

Rational investment is just one kind of behavior, making up barely 10 percent of a stock’s trading activity, Quast believes. The rest can be chalked up to speculation and risk management in a thousand hues.

One of the Occupy Wall Street movement’s complaints is that the market is broken, or at least rigged, and it’s a fear shared by many IR executives and their senior management teams.

Part of the problem is that – with inflation adjusted for – stocks have been a lousy bet over the last decade and more. There have been plenty of rallies and dips since 2000 and fortunes have been made, but retirement plans have languished.

The feeling is that in place of shareowners, the market has been hijacked by traders – price takers, not price makers.

There is also a lot of handwringing over the mechanisms that underpin a market dominated by computers.

For example, regulators have done nothing to guarantee the May 2010 Flash Crash won’t be repeated, and some doomsayers warn of a ‘splash crash’, which would simultaneously decimate stocks, bonds, commodities and other assets.

Common concerns for IROs

At IR Magazine Think Tanks and conferences in the US, Canada, Europe and Asia over recent months, the two most common discussion points were volatility and short-termism.

IR professionals are concerned about wild, unexplained stock swings; they believe portfolio turnover among even long-term investors ramped up after the financial crisis and again last summer because of European debt concerns and the US debt downgrade, and they wonder when – if ever – investment time horizons will recede back to normal.

Analysis conducted for IR magazine by Ipreo, a market intelligence provider, reveals the big picture – and it’s a surprisingly cheery one.

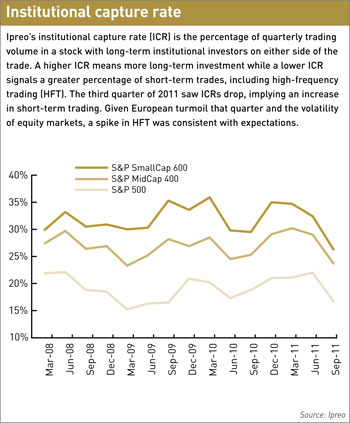

Despite rising trading volumes, the average institutional capture rate – the proportion of an issuer’s trading volume involving long-term investors – is back to pre-crisis levels for US stocks.

In other words, HFT made a lot of noise in times of great volatility but overall it’s not getting any worse. It may even be drying up a bit as new entrants chip away at the space.

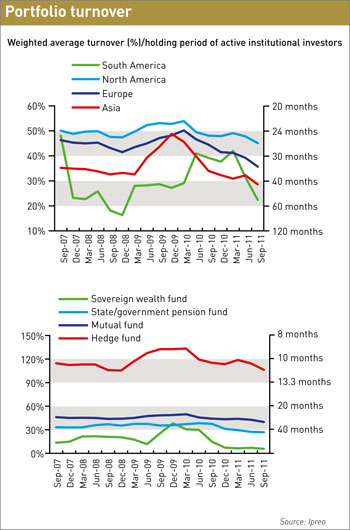

More significantly for IROs, the portfolio turnover of the world’s active equity managers has steadied to a level below where it was in 2007, before the US housing collapse and all that ensued.

This is true for North America, Europe and Asia, and for different kinds of investors, even hedge funds. Sure, some mainstream investors have shortened their horizons, and fast-moving hedge funds have proliferated, but data show that momentum players are more than balanced out by long-term buy-and-hold institutions.

Hard to explain market moves

No one can figure out exactly why the stock market has been whipsawing so badly in recent years, and particularly since August 2011 when European debt concerns were joined by the US debt downgrade and the stock market took off into hysteria, with unprecedented consecutive day swings greater than 4 percent and an average for the month of 2.2 percent.

Some experts believe high volatility may be the ‘new normal’, a state the market slipped into some time in the last decade. A New York Times study finds that since 2000, 4 percent daily moves in the S&P 500 have happened six times more than on average in the four previous decades.

The best guess about the extreme market swings since last August is that they were born in jumpiness around macroeconomic factors and then amplified by HFT, other kinds of program trading and, perhaps, exotic exchange-traded funds based on derivatives.

A lot of IROs’ frustration is because of record-high correlation, with stocks moving almost in lockstep with indices regardless of their fundamentals.

The 50-day correlation of S&P 500 stocks to gains or losses in the full index broke record after record during August and September 2011 to peak at 0.86 in October, according to Connecticut-based Birinyi Associates (a correlation of 1 would meanall 500 stocks moved together).

‘Dating back to the financial crisis, so much of the discussion with investors has focused on macroeconomic concerns, companies don’t think they’re getting their story across effectively unless it’s connected to a particular macro story,’ says Chris Taylor, head of global investor relations services at Ipreo.

Macro effect

This macro effect reached new heights in 2011. ‘Everyone was running around in a mad panic most of the second half of the year, with fund managers obsessing about macro issues,’ says Adrian Rusling, partner at Phoenix-IR in Brussels.

‘It was more difficult to get investors to think in the bottom-up way you want them to.’

No wonder IROs thought investors were losing their long-term focus. But Rusling says there is also some distortion at play.

‘The perception of short-termism is further augmented because the sell side is driving companies toward the highest-turnover investors,’ he suggests.

‘Let’s not forget there are still plenty of long-term, fundamental investors out there. We actually get complaints from some of them that they’re being overlooked.’

Ipreo’s close study of the data shows spikes in trading volume – such as in Q3 2011 – were not matched by spikes in institutional turnover, even while more HFT takes advantage of the volatile conditions.

‘High market correlations may force portfolio managers to stay put in a macro-driven market given that there aren’t really many safe investments to go to other than cash,’ says Brian Matt, director of data strategy and analytics for Ipreo.

‘So periods of high correlation actually showed lower portfolio turnover. Plus we’ve seen overall portfolio turnover trending lower generally since mid-to-late 2009.’

Comfort for IR in low turnover

This evidence of lower turnover portfolios should comfort IROs. Despite all the macro hiccups and extraneous trading noise, the tenets of investor relations are holding firm.

‘We’re still focused on strategies to get management teams in front of the most suitable long-term institutional investors,’ Taylor sums up. ‘Our clients are sticking to their knitting.’

Looking back several years, further than Ipreo’s study does, Mike Haase, vice president of investor relations and treasury at VMware, a $39 bn technology company in Palo Alto, California, has seen many traditional, long-only investors gradually take a shorter-term view.

‘But even if their average holding period has come down, they’re still a lot longer term than momentum investors, hedge funds and so on,’ he says. ‘The gap is smaller but still meaningful, and the IRO’s role in targeting the best shareholders is all the more important.’

It’s not enough to seek out long-term investors. The other side of the short-termism story is how companies are run, and over the last year they’re been as much at the mercy of macro curveballs as investors.

CFA Institute and Business Roundtable produced ‘Breaking the short-term cycle’ in 2006, recommending an end to earnings guidance and a switch to longer-term incentives and, in looking back, the shock is how little things have changed.

Recognizing the obstinacy of short-termism, CFA Institute is now working on a follow-up model. ‘We want to focus on what boards and management can do in the face of these pressures,’ says Matt Orsagh, CFA Institute’s director of capital markets policy.

‘They have to manage for the long term, and they have to communicate that long-term strategy. I’m surprised it doesn’t seem to be happening as much as I would have expected.’

Chinese shortsShort-selling is considered a scourge by many IROs and barely tolerated by the rest. Complaints from companies since the financial crisis prompted regulators in Europe and the US to try to curb short-selling, with little effect. In Asia, Hong Kong and South Korea have both moved against the practice.As for China, it introduced limited short-selling in 2010 and now the China Securities Regulatory Commission is expected to unveil a new Centralised Securities Lending Exchange as soon as March 2012, making short-selling easier and cheaper. Why is China swimming against the worldwide current and embracing short-selling? ‘When regulators see short-selling bringing in distortion, they bring in restrictions. But at least short-selling is an option in those markets,’ says Anindya Chatterjee, senior portfolio manager for Rochdale Investment Management’s emerging markets fund. ‘China realizes it needs short-selling to improve price discovery, market depth and liquidity. It’s a necessary evil.’ China is expected to keep tight reins on short-selling and to clamp down on excessive speculation or manipulation. ‘It’s an important dimension for equity markets, but that does not mean it will be unbridled and unregulated,’ Chatterjee adds. Commentators say the new short-selling regime will boost China’s domestic hedge fund industry, though Chatterjee predicts no dramatic growth in the near future because the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets are still dominated by individual investors unused to handing over their money to professional money managers. |