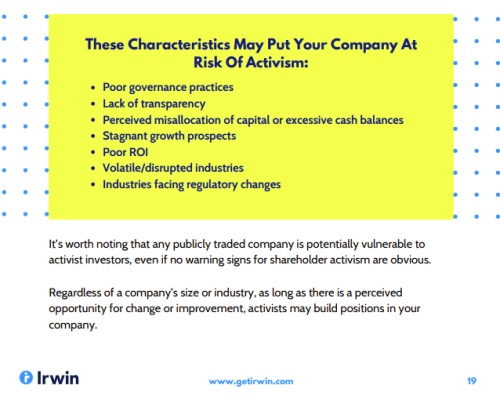

IROs attempting to target SWFs have to contend with their widely varying investment style and behavior, as well as having to overcome their lack of transparency

With more than $3 tn in assets, the world’s sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are becoming a prime source of potential investment capital. Just look at Citi, Merrill Lynch, UBS, Credit Suisse, Blackstone, Carlyle Group, Time Warner, Barclays and Standard Chartered, which have all partnered in major deals with a variety of government-directed funds.

But can you get in front of SWFs if you don’t have a marquee name? The answer is, well, maybe. Many SWFs have portfolios with minority equity investments, just like pension and mutual funds. Some have representatives in New York or London, and others welcome visits to their home-country headquarters. Many farm out their investments to mainstream intermediaries. In fact, there is no such thing as a typical SWF. Each has its own unique investment philosophy, management style, disclosure level and, above all, strategic objective.

Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates all have SWFs managing their vast reserves of oil money. Norway also has an oil-fueled pension fund designed to provide national income. China established its SWF to put excess foreign exchange assets to work.

Others, like Abu Dhabi and Singapore, use their funds to reshape their economies, and controversy has followed some state entities – Russia, primarily – because of the suspicion that investments are being made for geopolitical advantage rather than economic return. New funds, like Chile’s, are springing up with their own objectives.

Investment philosophies range from conservative, long-term stakes in liquid securities to riskier private equity, real estate and hedge fund maneuvers. Some SWFs buy private companies outright, or take a controlling interest in public companies.

Tough target

Finding holdings data and contact details for SWFs can be difficult. ‘In a lot of cases you don’t really know how much money they’ve got in equities, let alone the breakouts of sector exposure or individual holding positions,’ says Adrian Rusling, a partner at Phoenix IR in Brussels.

The Monitor Group’s Bill Miracky, whose firm has just studied decades of SWF investments, goes further. ‘You don’t have the depth of information about what they have done, nor are they very explicit about exactly what they’re interested in,’ he warns.

Despite this level of opacity, however, IROs can get directly in front of decision makers from the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation, the Kuwait Investment Authority, and Norway’s Government Pension Fund, all of which have offices with investment teams in New York or London.

‘These are people who have been running what you and I would call mainstream equity portfolios for years,’ Rusling says, going on to describe their investment process as ‘very rigorous and long-term-oriented. They are going to look at the themes they like, and then they are going to want to meet management and understand strategy, rather than crunching through a spreadsheet workout of that quarter’s earnings. They’re not focused on the short term, as a US fund would be.’

Rusling says name recognition can help get an IRO in the door. ‘I wouldn’t necessarily rule out smaller-cap companies with a great story, but obviously it is a top-down approach and most of these institutions are looking at larger-cap names,’ he explains.

Hitting the trail

Neil Doyle, managing director of Capital MS&L’s Middle East office in Dubai, says that after the first ‘natural port of call’ in London, institutions like the SWFs of Singapore and Abu Dhabi are usually happy to welcome management teams to their home markets, where they have bigger teams of fund managers.

IROs on a visit to the Middle East ‘shouldn’t expect to see the packed agendas they are used to in US, European and Asian markets,’ Doyle says, as few funds other than the largest ones take an interest in non-deal roadshows by firms from outside the region.

Tom Kusner, a data director for market intelligence specialist Ipreo, says it can take time to get past the gatekeepers in order to reach the decision makers. ‘Call them intermediaries, call them managers, call them advisers – whatever they are, these gatekeepers sit between companies and the fund,’ he says. ‘I guarantee you’re not going to get in front of them without shaking several hands first.’

There’s an alternative to cold-calling SWFs yourself, according to Jack Carsky, head of global investor relations for Visa, who played a role in the company’s massive worldwide IPO in March. ‘The best place to start is with your bankers,’ he says. ‘Let them put out some feelers via their sales force and figure out whether there really is an interest. To me that would always be the first and best avenue for figuring out if they even want to see you. Plus, do they just want to see you out of curiosity, or is there something there that could lead to a longer relationship?’

Take it to the bank

Getting the bankers to help can save time and energy. Visa picked JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs to market its offering in Asia and the Middle East, and the already established relationships between the company and these banks helped. ‘Trust me, if there is an opportunity to be had, the bankers will be more than happy to make it happen,’ Carsky says.

Even with such heavyweight help, Carsky thinks it would be difficult for smaller companies to get into the SWF mix. SWFs want to focus on recognizable brands, and with the large size of SWFs and thus the large size of a meaningful equity stake, smaller companies may be less attractive.

According to the Monitor Group’s study, financial services are far and away the most popular sector. ‘A lot of the money is in Singapore and Dubai, which are the big financial centers, and these are players in financial services themselves,’ explains Miracky. ‘It’s what they know.’

Many of the experts note that SWFs are not a new phenomenon – it’s just that mushrooming oil money in the Middle East and huge new pools of capital in Greater China are grabbing headlines. As best practices evolve, SWFs will start to meld with your shareholder base as seamlessly as any investor.

Ted Truman’s guide to working with sovereign wealth funds

SWFs may be good for the US economy and for many individual companies in general, but naysayers voice concerns about countries with varied ideologies and interests having significant holdings in US companies.

Edwin ‘Ted’ Truman, a senior fellow at the Peter G Peterson Institute for International Economics, a private, non-profit, non-partisan group headquartered in Washington, DC, is a leading advocate for best practices and transparency among SWFs. He served as assistant secretary for international affairs at the US Treasury from 1998 to January 2001 after handling international finance for the Federal Reserve.

How should an IRO deal with shareholders who are nervous about SWFs investing in their company?

I think the solution is the same as that advocated by me and others who are pushing for best practices. The clearer a fund’s objectives and structure, including how it is governed and its level of accountability, the greater comfort IR can offer to parallel investors. If the track record is there, it’s really no different from investing alongside Fidelity, for example, or another large investor.

Are SWFs forgoing board seats and other trappings of ownership that traditionally come with large investments?

In some cases, that is true. Many of these funds do have board seats, however, and some have controlling interests: at least a dozen SWFs own controlling interests in companies. Giving up board seats is a way of attempting to appear less frightening and encouraging protectionism – but if the fund owns 9.9 percent of a company, it doesn’t need a board seat to have influence.

In your May testimony before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, you said SWFs might contribute to market turmoil and uncertainty, but they might also contribute to financial stability. How can a company know whether an SWF will be a positive influence or a disruptive one?

It’s impossible to generalize about SWFs as they have such varying investment strategies. They might also have different views on what their market responsibilities are. Some have articulated rules about how they adjust their portfolios, for example, so they are mindful that they need to be sensitive to market conditions. Very few have a publicly stated policy, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have a policy.

Who are the people typically running the investment strategy of the SWF, and are they hard to communicate with?

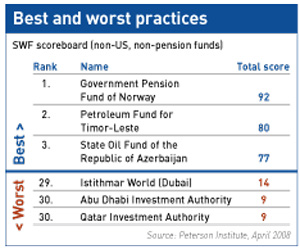

This is part of the whole accountability debate. My impression is that funds of any size increasingly realize they have to have their own PR/IR strategy, whether that means just issuing more press releases or going to the extent of adopting Truman-style best practices. If the media are going to find out anyway, it’s better to get the information out on your own terms. I think the funds are realizing that, and communication is becoming somewhat easier. You and your Peterson Institute colleague Doug Dowson have developed a scoreboard for SWF best practices (see Best and worst practices, right), rating funds on 33 elements in four categories: structure, governance, accountability and transparency, and behavior. Can companies use the scoreboard to better communicate with their shareholders about SWFs?

You and your Peterson Institute colleague Doug Dowson have developed a scoreboard for SWF best practices (see Best and worst practices, right), rating funds on 33 elements in four categories: structure, governance, accountability and transparency, and behavior. Can companies use the scoreboard to better communicate with their shareholders about SWFs?

That’s the logic: by being more transparent, by getting a high score on the Truman Index [as the Wall Street Journal has called the scoreboard], you are less threatening all round. Reporting standards based on the criteria we have outlined, along with a track record that your IR team can cite, can help put other investors at ease.