The devil is in the detail: it’s an adage that certainly applies to IROs understanding the share register. But given that understanding share ownership has become more complex over the last 20 years due to the significant growth in synthetic holdings by banks and other traders, hedge funds and – latterly – traditional institutional investors, there is much detail for IROs to understand.

‘The top priority for IROs regarding their shareholder base is to understand and connect with their audience,’ says Myles Clouston, senior director of advisory services at Nasdaq Corporate Solutions. ‘It is critical that IROs are keenly aware of the mix of investors that own shares and how reflective they are of the business narrative a company is trying to articulate,’ he says.

There is an advantage in understanding the hard data and analytics that drive investment decisions and how the IRO and management team can better highlight things that tell the investment story to the respective audience. ‘At the end of the day, companies are all competing for capital,’ notes Clouston. ‘Equally important is that the IRO is able to earn the respect of the investment community by demonstrating his or her knowledge, preparation and integrity.’

The many hats of an IRO

Taking the time and effort to build relationships with key current and prospective investors cannot be underscored enough, adds Clouston. ‘The ability to better understand an investor’s motivations, excitement and pain is invaluable in managing expectations and being viewed more strategically,’ he says. ‘IROs today wear more hats than ever so it is increasingly important that they are in tune with the investment community.’

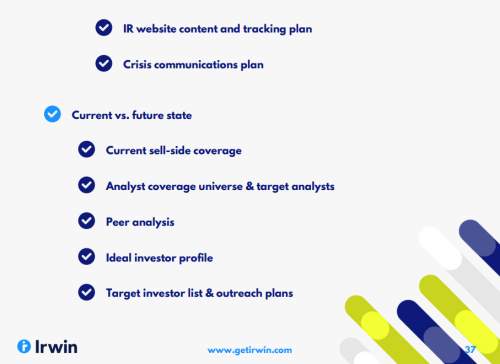

Nevertheless, Richard Davies, managing director of London-based RD:IR, notes that the fundamentals of IR still apply. ‘Understanding who owns your stock, and, as part of that, who is really buying and selling your shares, remains the foundation of the IR process, in whichever market you operate,’ he explains. ‘You need accurate and granular data on your share ownership in order to action thorough and deep investor outreach, carry out effective targeting and report insightfully on the relationship between your IR strategy and changes in your investor profile.’

Davies adds that IROs also need to understand the share register in terms of beneficial ownership as well as investment management, investor voting rights, the different types and investment styles of investors, where investors are based and from where they are managed, and how to differentiate between real investment positions and trading accounts.

Julian Cassells, president of New Jersey-based Alpha Advisory Associates, points out that ‘corporate issuers often misunderstand the share register. It largely provides a list of the cumulative bank and broker holdings, which some corporates inaccurately assume are the actual shareholders.

‘Visiting some companies’ IR web pages when they do disclose their top shareholders I can clearly see that they regurgitate the bank and broker holdings from the share register. To begin to dismantle this mistake, it is important to understand that the share register has a lot of layers of ownership beyond the bank and brokers.’

Peeling the onion

Cassells therefore compares the process to an onion, with its many layers: behind these banks and brokers are the actual shareholders and their funds.

‘Sometimes there may only be funds listed, and further research is needed to uncover the investors managing the funds, and there are instances where some funds are multi-managed,’ he says. ‘Once the ‘onion’ is carefully peeled back, corporate issuers can determine the cumulative number of shares held by each investor, whether it is institutional, hedge, retail, and so on, its geographical location, and the identity of the analyst/portfolio manager covering the firm’s sector. This discovery can be used as an effective tool to improving their IR efforts.’

Another factor in the ability to track share ownership depends on the market where the equity issuer is domiciled: some markets have more favorably transparent regimes than others.

‘All markets have some degree of ‘passive’ ownership disclosure as part of their market regulations but often these thresholds are too high – at say 5 percent or 10 percent of issued share capital – to adequately provide IR professionals with the levels of insight they need,’ Davies says. ‘The UK and many British colonies also have a helpful ‘active’ disclosure regime, where equity issuers can ask – or even force, on the basis of possible penalty – investors to disclose their interest in the company.’

Other markets may have a mix of provision to allow companies insight, sometimes with a penalty for non-disclosure, sometimes not. ‘The US is a ‘passive’ disclosure market but its Section 13F filing regime provides reasonable coverage of stock ownership, albeit often not in a manner timely enough for effective use, given that investors have 45 days after calendar year-end to file their positions,’ Davies continues.

‘Given the move globally toward increasing levels of passive and quantitative investment management, tracking the marginal buyer on the share register becomes commensurately more important.

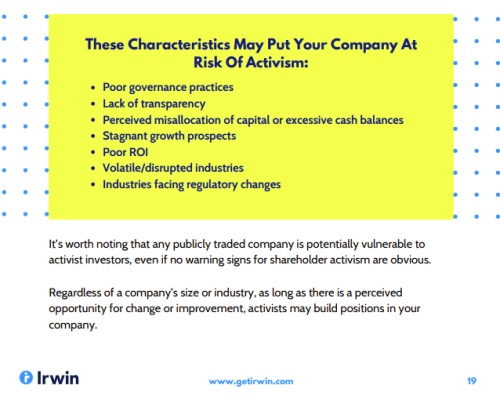

‘Investor relations professionals have a vested interest in retaining the highest possible levels of transparency in their markets with regard to understanding who owns the shares of their companies. This allows them to provide their boards with the best information for good governance and defense against predators or activists, maximize the demand for their stock to improve liquidity and understand better the efficiency of outcome of their IR approach.’