Reflections on a quarter-century of IR to mark IR Magazine's silver anniversary

My parents originally wanted me to be a lawyer, and in college I was lucky enough to get an internship with IBM in its corporate litigation department. Through this I had a chance to work with the best of the best and get a good view into what this life would be like, and what I discovered was that I really did not want to be a lawyer.

But part of my job there was to review the top technology companies in the world and assess how they were doing through their annual reports and financial presentations, and I realized that I really liked this whole Wall Street thing. So I went back to school at Brown and took all the economics courses I could find and set out to find a job at a Wall Street firm, eventually starting as a retail stockbroker for Janney Montgomery Scott. I think I might be the only stockbroker who never made any money for anyone; what’s worse is that I also lost all my friends’ and family’s money, as they’re the people I was selling to. I knew I had hit rock-bottom when I had to make a margin call on my grandmother…

So I went back to school at Brown and took all the economics courses I could find and set out to find a job at a Wall Street firm, eventually starting as a retail stockbroker for Janney Montgomery Scott. I think I might be the only stockbroker who never made any money for anyone; what’s worse is that I also lost all my friends’ and family’s money, as they’re the people I was selling to. I knew I had hit rock-bottom when I had to make a margin call on my grandmother…

After a slew of clichéd Ivy League occupations of which my parents are very proud – bartending, roofing and moving – I became a stock surveillance analyst at the Carter Organization, one of the premier proxy solicitation firms and a pioneer in stock surveillance. I loved the job: I loved having clients, I loved the pressure of having people rely on me for answers, I loved the investigative reporting aspect of it.

One of the first (and coolest) accounts I ever had was doing surveillance for a big defense contractor (that I will leave unnamed) which had heard rumors of Middle Eastern arms dealers taking a significant position in their company through a Miami bank, and it was my job to identify the shareholder. This was 1988, Iran-Contra, Adnan Khashoggi, guns for drugs – all kinds of intrigue. I was hooked!

Laying the groundwork

I started the Carson Group with Dave Geliebter at around the same time as IR Magazine launched its first issue. We were one of the early advertisers in the magazine; we wanted to get our name out there and IR Magazine was a great forum for doing that.

How we really got going, though, was by creating our Adopt-a-Client program where, unbeknown to the client, we would just start working for it by conducting analysis on its stock. When we alerted it that it had been part of our program, some yelled at us, but some listened.

Eventually we got a handful of companies to formalize our relationship: Sears, Lockheed and TransAmerica, which was enough to get us references to help win more clients. It was a great day when Dave called me from Michigan and said Dow Chemical had agreed to sign up, and two hours later I landed MCI. From there we were off and running.

In 1991 we went to our first NIRI conference. There were maybe 12 booths in total, all as staid as could be. Dave was a marketing genius and had all of these ideas about making our booth really exciting – TV sets, raffles, computers – all stuff that sounds passé today but was cutting-edge compared with standing there handing out business cards.

I started getting excited about it, but when I landed in Orlando, Dave picked me up at the airport and drove us to the lumber yard. That’s when it dawned on me that he and I were going to build the booth ourselves! It’s a good thing NIRI lasted only three days as the balsa wood was collapsing and we were trying to hammer things back into place while people were off at panel sessions.

Someone recently asked me whether I thought I could still conduct stock surveillance myself today. The last time I physically tracked a share was probably AIG in 1992 (for legendary CEO Hank Greenberg, who was extremely interested in every minute movement of his stock and once even made a ship-to-shore call to me on the day after Thanksgiving to demand an explanation for why his stock was down three quarters of a point on the 4,000 shares that were actually trading).

As I think about our analyst teams today, stock surveillance is dramatically different, both easier and more difficult. The obvious aspects of more difficulty involve the sheer volume of shares that trade on any given day, and the speed of the transactions. Also, separating the news from the noise is much more challenging.

Having said that, the tools our analysts have available to them are beyond anything I ever had, providing the ability to aggregate data very quickly and sift through an immense amount of information. So they have more to account for, but they have much better tools to do it with.

I always had a dream when I got into this business that one day we would be able to work with a global account and be able to wake people up in the morning with answers and tuck them in at night with answers, because we’d have analysts around the world who could provide continuous service. And today that’s actually the case.

Humble beginnings

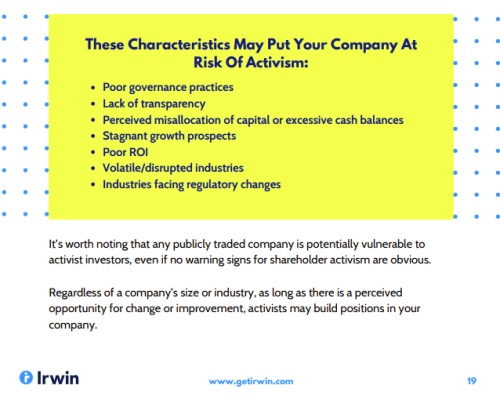

But prior to the early 1990s, proactive IR didn’t even exist; it wasn’t a given for companies that talking to shareholders even merited anything. In 1993-1994 we had the years of transition, triggered by the rise of the activist shareholder and driven by the twin motivators of fear and greed.

Titans of industry – CEOs at the likes of Sears, IBM and GM – were losing their jobs as shareholders started forcing a rethink of corporate strategy (fear), while executives were finding a greater portion of their compensation was being tied to stock performance (greed). Generally speaking, the companies to first embrace the concept of proactive IR were the ones that had just come through major proxy fights, like Lockheed and Texaco, and knew they had just fought for their lives.

The company that really stands out to me as a pioneer is GE. Jack Welch bought into the idea of being proactive in your story and understood that you could develop messaging around a conglomerate with disparate businesses and actually get a premium rather than a discount. P&G was another early adopter.

These were firms that realized, ‘We need to be doing this on a recurring basis, not just during a hostile situation. The mind of the shareholder is something we need to be on top of, all the time.’

Scott Ganeles is CEO of Ipreo.