As the US system for concealing beneficial shareholder's identities faces overhaul, do the benefits of more direct communication with shareholders outweigh concerns over privacy?

No matter how brilliantly IROs refine their techniques, they keep bumping up against brick walls. Communicating directly with shareholders is one of these perennial barriers: too often, efforts to ID investors resemble a game of Battleship, where names and contact details are discovered only by guesswork.

No wonder, then, that there are moves afoot to unmask beneficial shareowners who own their stock in ‘street names’ through a nominee broker. In April 2004 the Business Roundtable petitioned the SEC to make it easier to have direct communication, particularly with objecting beneficial owners (OBOs), but also with non-objecting beneficial owners (NOBOs). More recently, the NYSE Proxy Working Group asked to revisit the issue. One popular suggestion is that investors be solicited again to make sure they understand their NOBO/OBO status.

OBOs are ‘not a front burner issue with the SEC,’ explains Linda Kelleher, executive vice president of NIRI. ‘Commission chairman Cox has a few initiatives he’s very anxious to shepherd along as far as he can before a change in administration. And I don’t think NOBOs/OBOs are critical to him.’ Another individual closely connected to the issue puts it more bluntly: ‘Nothing’s going to happen until after the next US election.’

Hidden depths

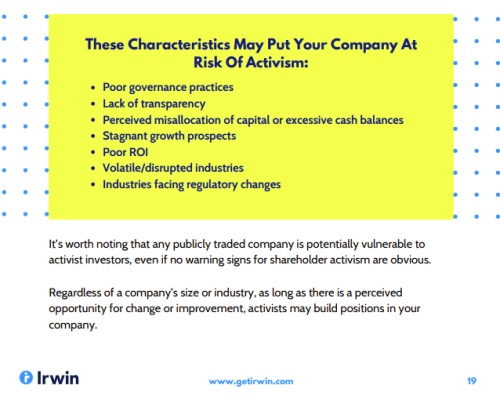

The veil of anonymity protecting investors is particularly galling to US IROs given that their colleagues abroad enjoy more shareholder information (see How OBOs fare in the UK, below). ‘It’s a constant frustration to our members that they don’t have a working knowledge of who their investors are,’ Kelleher says. ‘It’s particularly traumatic as the pace of electronic markets and the rise of hedge fund activism make this information more critical.’

Most feel the arguments favoring greater shareholder disclosure have recently grown more pressing. One finding of the NYSE Proxy Working Group, according to David Berger, partner at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati and the group’s counsel, is that a surprising number of investors don’t understand the NOBO/OBO distinction.

An April 2006 study conducted for the NYSE found only 20 percent of OBOs remember being asked whether they wanted their contact information provided to the companies whose stock they purchase. Of those, 79 percent provided contact information. Overall, 73 percent of investors surveyed either provided contact information or would have provided it had they been asked.

But these findings don’t jibe with current OBO numbers. Chuck Callan, senior vice president of regulatory affairs for Broadridge, says around 60 percent of account holders are NOBOs, so their names are available to any company that wants to buy its list from Broadridge. That said, Callan notes that only one third of shares are held by NOBOs, a disparity explained by the fact that many OBOs are large institutions that haven’t given permission to be identified.

Kurt Stocker, chairman of the NYSE Individual Investor Advisory Committee, agrees there’s a need for investor education. ‘The research clearly shows the majority of OBOs don’t know they’re OBOs and, when given more information, they don’t want to be OBOs,’ he says. In the absence of a clear preference, Stocker says the default should be NOBO, not OBO.

Changes looming on the proxy landscape are making direct communication a cause célèbre. The repeal of NYSE Rule 452, which should soon remove the broker discretionary vote for director elections, creates greater incentives for individual investors to vote because shareholders now have more power regarding critical board decisions. If retail investors don’t participate, however, institutions might wind up with greater say in the post-452 world.

‘If we’re going to remove broker discretionary voting, you have to allow issuers to have greater access to their shareholders through removal of the NOBO/OBO distinction,’ explains Berger.

Meeting and greeting

Charles Rossi, executive vice president of Computershare and president of the Stock Transfer Association, raises a related point. The elimination of Rule 452 means firms may soon need to approach shareholders far more frequently to generate the necessary vote in director elections. Given that proxy communications go through intermediary Broadridge, and that Broadridge’s rates haven’t been subject to competition, repeated communication could be ‘very, very expensive,’ Rossi cautions.

Rossi and Paul Conn, Computershare’s president of global capital markets, would both also like to wave goodbye to NOBO/OBO terminology, which they feel further clouds an already arcane debate.

The strongest supporters of the NOBO/OBO system are the brokers, who arguably exercise a stronger claim on their clients by controlling the communication flow. Most brokers, however, insist their interest is in protecting their clients’ privacy. ‘The brokers fervently argue that their clients do not want to be bothered by continual mailings and phone calls from companies soliciting during proxy season,’ explains Berger.

On the flip side, Stocker notes that companies don’t currently deluge direct investors with calls and junk mail; he insists there’s no reason to believe this would happen were direct communication permitted.

One offshoot of the privacy argument is that some fear throwing open shareholder rosters might also allow activists and hedge funds to communicate directly with their investors. Worst case scenario? In 2006 an animal rights group demanding that drug companies end all animal research sent GlaxoSmithKline’s shareholders menacing letters. The letters threatened to publish on the internet the names of all investors who refused to sell their Glaxo shares.

The potential risks of making shareholder lists too public have prompted some to advocate gradual change, and most people aren’t arguing against shareholder anonymity. As public companies incur considerable costs communicating through brokers and Broadridge, however, some suggest shareholders might retain their OBO status at a small price. Rossi compares this with paying for an unlisted phone number.

Whatever the solution, proponents of NOBO/OBO reform wish the problem garnered more attention. ‘I can’t tell you whether the NOBO/OBO question will be revisited,’ concludes Stocker. ‘But I can say that it should be.’

How OBOs fare in the UK

American companies often have a far easier time identifying non-US investors than US ones, observes Mark Hynes, managing director of IR services at PR Newswire in London. ‘Regulations outside the US are significantly more beneficial to the company in terms of identifying shareholders than they are inside the US,’ he says.

After revisiting the non-objecting beneficial owner (NOBO)/objecting beneficial owner (OBO) distinction a few years back, Canada instituted NI 54-101, which took effect in February 2005. The law allows issuers to distribute proxy materials directly to NOBOs so companies no longer bear the added expense associated with communicating with street-name holders.

In addition, Hynes says in countries like the UK, Australia, South Africa and France, companies have a right to demand that investors disclose their position.In the UK, such inquiries have been fair game since 1993, thanks to Section 793 of the Companies Act.

If a bank or broker refuses to give out this information, a British issuer can apply to the courts to withdraw the objecting shareholder’s dividends and even withhold his/her vote, thereby disenfranchising the shares.

There are signs, too, that the investor knowledge gulf between the US and other countries may soon widen. The UK regulator, the Financial Services Authority, recently published a consultation paper suggesting that investors with an economic interest in a firm through contracts for difference or other derivatives could be required to disclose positions above 3 percent. Such a change, says Hynes, would be a major boon for UK IROs.