Who do IRO's love to see on their list of shareholders?

Shareholder envy can be a bitter pill to swallow. This is especially true for companies that always attract the usual suspects – those that up their stake on the sly or badger IROs for tempting yet unrealistic demands to change the CEO or relocate to Monaco. A trifle galling, when there are IROs who effortlessly clock up scores of low-maintenance, high-revenue investors. IR magazine is on hand with a few tips to help decipher which potential shareholders to target – and which to avoid.

In it for the long haul

Long-term investors are a strong favorite as they offer stability, patience and ongoing support. It takes more than poor quarterly earnings to faze the long-term investor, who tends to be a dedicated follower of company strategy.

Institutions with low turnovers top the list of preferred investors for global market intelligence provider Ipreo. ‘They are all potential long-term holders of any equity, as long as it doesn’t exceed an established price ceiling,’ notes Cary Krosinsky of Ipreo. ‘They are seldom activist. Morgan Stanley is the rare exception, as we saw when it tried to change the structure of the New York Times.’ New York-based asset manager AllianceBernstein is one of Stora Enso’s most valued long-term investors. ‘It appreciated the fact we paid it a house call, instead of just meeting it at the conference, as we did with the other investors,’ remarks Stora Enso IRO Keith Russell. Being a valuation-driven investor, Bernstein upped its stake when Stora Enso shares fell in value, actually misjudging the possibility of further decline. ‘But instead of grumbling about the loss involved, Bernstein concentrated on the future,’ comments Russell.

New York-based asset manager AllianceBernstein is one of Stora Enso’s most valued long-term investors. ‘It appreciated the fact we paid it a house call, instead of just meeting it at the conference, as we did with the other investors,’ remarks Stora Enso IRO Keith Russell. Being a valuation-driven investor, Bernstein upped its stake when Stora Enso shares fell in value, actually misjudging the possibility of further decline. ‘But instead of grumbling about the loss involved, Bernstein concentrated on the future,’ comments Russell.

Not all IROs swear by long-term investors alone, however. Moscow-headquartered telecoms group MTS is keen to involve other investors in its growth story. ‘We’ve experienced a 29 percent growth rate in the last few years and we’re paying our first $1 bn-plus dividend at the end of the year,’ enthuses Joshua Tulgan, head of IR at Russia’s largest float. Yet he admits the group is too unconventional for a lot of investors. ‘Many won’t invest in Russian stock because of corporate governance issues or our actual geographic location,’ he says.

MTS still has long-term holders, such as London-based Genesis, which has been with the company ever since its IPO in 2000. Capital Research & Management Company and Fidelity are also long-term shareholders in the Russian telecoms giant. ‘While some organizations might allow us contact with their telecoms analysts only, giving us limited access to the group as a whole, Fidelity is good at bringing in different portfolio managers to offer us wider variety,’ remarks Tulgan.

Few long-term investors opt for the hands-off approach but, surprisingly, not all IROs welcome low-maintenance shareholders. Templeton Investment Council has invested in Stora Enso for the past six years, but has minimal contact with the company. ‘The worry is that if it decides to reduce its stake you don’t see it coming,’ says Russell.

Size does matter

Many IROs would beg to differ and view quiet funds, flush with cash, as dream investors. When Boston-based Acadian Asset Management came out of the woodwork and bought 11.5 mn shares in MTS, Tulgan tried to pay it a visit – but it didn’t want to see him. ‘It’s the best possible combination: buying enough shares to become our number one minority shareholder and not even needing to be seen!’ he jokes. Since Acadian had also invested in MTS’ competitor, Tulgan deduced it was opting for a sector specialization dictated by black-box metrics.

While Tulgan landed himself a new top minority shareholder without having to lift a finger, Russell has been working away at Brandes Investment Partners in California even though it has yet to invest in Stora Enso. ‘We’ve met it about 10 times, but it is still not a shareholder as we’re not cheap enough,’ explains Russell. ‘Its potential is enough to convince us to spend time on it.’

Does investment size justify extra attention? Some take a dim view of smaller hedge funds that make a lot of noise. ‘They punch well above their weight, demanding management time,’ complains Russell, who feels buying a bigger ticket shouldn’t automatically give investors the right to challenge the board. ‘However much investors think they know, it doesn’t compare with inside information.’

Hedge funds suffer a pretty bad press for encouraging their friends to join them in a stock and then blatantly self-servicing – especially those that short stock and then rumor-monger to get shares to go down. They’re not all bad news for IROs, though, particularly the ones that talk shares up. ‘Hedge fund investors in MTS, such as New York-headquartered Black Rock and San Francisco-based Standard Pacific, are in touch regularly, and this helps enormously with relaying information to management as well as finding out shareholder interests and intentions,’ says Tulgan.

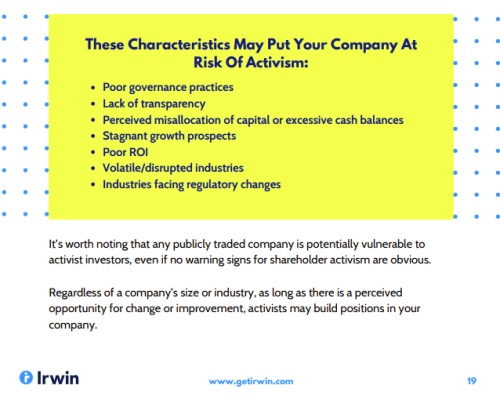

Hedging your bets For IROs in need of liquidity or volatility, hedge funds do help get things moving. They often enter into the story earlier and start building momentum. Even activist funds aren’t necessarily to be feared. MTS’ largest shareholder is Sistema, a government-owned body that is publicly traded and has its fair share of activist shareholders.

For IROs in need of liquidity or volatility, hedge funds do help get things moving. They often enter into the story earlier and start building momentum. Even activist funds aren’t necessarily to be feared. MTS’ largest shareholder is Sistema, a government-owned body that is publicly traded and has its fair share of activist shareholders.

‘Many of them come to see me to put their views across,’ says Tulgan. ‘I don’t always agree with them, because they just want to maximize value for Sistema, whereas my job is to look after all the shareholders.’ Minority investors drive the value of the company, he adds.

Sadly, there is no such thing as the perfect shareholder. The quietest, least bothersome investors can turn out to be every IRO’s worst nightmare. Similarly, the more demanding and irksome shareholders can come to a company’s rescue in the most unexpected circumstances. The key is to keep a careful watch on your investors, even those that don’t want to see you.

This is easier said than done for some companies. As Krosinsky points out, not only is institutional ownership more visible in the US, but so typically are the activists in question, as they would need to file a 13D with the SEC for any potentially activist position in excess of 5 percent. In the UK and Ireland, however, controversial contracts for difference are still rife, allowing activist shareholders to secretly build up a stake in a company and force through change.

Like a lot of things in life, a good balance is the best bet for most IROs. A mix of passive and active, with both long-term and short-term shareholders, will help cover any eventuality. And of course, even if your share price isn’t going well at the moment, there are some investors you can always rely on for a good time – see IR magazine's article, Reaping the rewards of the right investor, for some examples.